While Gov. Jerry Brown and lawmakers wrestle with the budget crisis, some Californians are adamant that much of the problem can be laid at the feet of people who are in the country illegally.

Their message is: stop teaching the kids, cut-off welfare checks and ship the prisoners back home.

That way, billions of dollars spent on services could be put to work cutting the deficit, paying for vital programs and keeping tax increases at bay.

But that’s easier said than done.

Court rulings require California to teach every child regardless of citizenship. Ditto for treating emergency cases in the hospital. All children born in this country are citizens, so counties are required to provide cash aid and other services, even if their parents are here illegally. And the federal government has been pretty stingy when it comes to reimbursing states for the rising tab.

California is home to more undocumented immigrants than any other state. There were nearly 2.6 million here in 2010, according to the Department of Homeland Security. More than half are from Mexico.

With so many here, there is certainly a case to be made that taxpayers cover billions of dollars, mostly for classrooms, hospitals and prisons.

But there is an equally sound case to be made that, while here, many illegal immigrants pay into the system, from sales tax on clothes to property tax on homes. Many paychecks are docked for Social Security that likely will never be collected.

There have been a handful of studies from the left and right, as well as a report by the Congressional Budget Office, assessing the cost and contributions of undocumented immigrants. But none has been received as definitive.

In California, the closest to an unbiased review is offered by the state Legislative Analyst’s Office. The nonpartisan analyst pegs the state’s costs at $4.2 billion. But even then, some information is imprecise, mostly because accurate figures are hard to come by.

In an interview, Deputy Legislative Analyst Dan Carson, who tracks the issue, said it is impossible to pinpoint how much could be saved, given legal constraints.

In many instances “you need federal and court” action, Carson said. Also, big savings are accompanied with major policy headaches, such as how to release prisoners or how to refuse vital medical care.

Consider the prisons. It’s one thing to deport inmates once they have done their time and are about to be released. But sending convicted felons back home, with no guarantee that they would serve their sentences, would be giving them lighter treatment than legal residents who commit the same crimes. It is conceivable that a convicted murderer could be deported, released by his home country and return to California to offend again.

Anti-illegal immigration lawmakers are not convinced. They believe the state exaggerates the barriers to taking action -– mostly to avoid riling a huge Latino constituency.

“That’s a dodge. We’re not handcuffed,” said Assemblyman Tim Donnelly, R-Twin Peaks, an outspoken critic of immigration policy. He believes the state could find billions if policymakers could only muster the will. “There’s a lot we can do, but it’s not politically correct to do it,” Donnelly said.

Donnelly said he does not advocate tossing kids out of class or refusing to treat seriously hurt undocumented aliens. He also recognizes the legal obstacles.

Rather, he proposes a broader, long-term strategy ranging from more border enforcement to a Marshall Plan to invest in Mexico. Many of the measures he advocates would likely have to include actions by the federal government.

That includes tougher verification of immigration status before hiring. He also favors a guest-worker program with caveats. Among those: allow workers to come here as long as they go back to their home country first. They would have first-call on entry since they already have a job. But they would have to take their family home and leave them there to make sure taxpayers are not billed for services.

That would also produce more income taxes for the state by limiting the underground economy, he said.

Donnelly said there are savings to be had immediately. For example, stepped up verification of status could also save taxpayers millions by eliminating fraudulent collection of aid. Those here illegally also should not be allowed to use hospitals for routine care.

The conservative-leaning Federation for American Immigration Reform estimates that the national bill for undocumented immigration is $113 billion every year. Of that, California’s share is $21.75 billion, including state and federal costs. That figure takes in the cost of services, from education to housing assistance to medical care, as well as law enforcement to patrol borders and keep criminals in jail. The group said contributions from those here illegally, such as paying into Social Security and other taxes, amounts to $13.4 billion.

The report, compiled in July 2010 and revised earlier this year, used as its foundation an estimate of 13 million people in the country illegally. The FAIR study drew on existing census information and extrapolated various costs associated with everything from courts to schools to welfare. But it also included costs of migrant education, the immigration review office, the National Guard and Coast Guard.

The state Legislative Analyst study was not as broad, keeping its research focused on the state’s largest program costs.

The Congressional Budget Office in December 2007 released an analysis of 29 various reports over 15 years. The federal office concluded that “state and local governments incur costs for providing services to unauthorized immigrants and have limited options for avoiding or minimizing these costs.”

Also, the federal office determined that taxes paid by undocumented immigrants do not offset the cost of services and federal aid does not fully repay states for expenses.

San Diego State University professor John Weeks, in a 2006-2007 study, estimated that it cost San Diego County $101.5 million that year to provide services. About three-fourths of that was related to law enforcement, he said.

Legal residents paid an average of $38.15 in taxes toward the bill in 2007, Weeks estimated. The population in the county illegally was placed at nearly 210,000 in 2007 – more than double the 1990 estimate.

Costs aside, contributions have to be part of any debate, Weeks said in an interview this month. Forcing immigrants to leave, he said, would be a blow to the economy given the kinds of jobs they are willing to do and taxes paid.

“Certainly sending people back to Mexico would not solve the budget crisis. It would only make it worse,” Weeks said.

“Undocumented immigrants are not a problem for the American economy. If anything, they are a bonus,” Weeks said. He called them an “exploited class” who provide “goods and services at a cost we otherwise couldn’t afford to pay.”

Critics counter that with so many legal residents out of work, the jobs could be filled quickly. More importantly, the broader philosophical belief remains: why reward someone in this country illegally? Providing services only encourages more to cross the border without papers, they say.

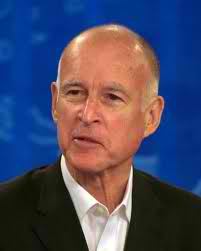

Gov. Brown straddled the middle when asked about the cost of illegal immigration.

“It s a difficult question,” he replied. “There are a lot of undocumented people working and paying Social Security and they never collect it. They work at wages Californians wouldn’t otherwise (accept) … Then you have the ones who graduated from our schools and are making enormous contributions … So you’ve got to net out. What the net is is, is a matter of dispute. Conservatives say it’s one thing and more liberal minded people say it’s another.”

And what does he say?

“I don’t think the evidence is clear,” Brown answered.

California Legislative Analyst

The nonpartisan Legislative Analyst, using data from the 2008-2009 fiscal year, concludes that the bill for providing services to undocumented immigrants and incarcerating those convicted of crimes is about $4.2 billion. The report did not measure how much could be saved if certain services are eliminated, but savings would certainly not approach that figure because many programs are required by Congress or the courts.

Spending on illegal immigrants primarily falls into the following five areas:

K-12 Schools: The cost is $1.9 billion. In California, 4.3 percent, or 270,000 children, are here illegally. . The courts have ruled that education is a right regardless of residency status.

Prisons: Spending reached $1 billion, but the federal government reimbursed just $100 million of that. (Separately, the California Department of Corrections reports there are about 18,300 “deportable felons” in state prisons. The vast majority – nearly 16,000 – are Mexican citizens. The average cost? $44,563 a year per inmate.)

Medical services: The $775 million cost is primarily driven by emergency care at hospitals, which is reimbursed by the state. Hospitals are prohibited from denying service based on residency status. Lawmakers could save money by deleting some services, such as cervical and breast cancer screening. However, the biggest expense – baby deliveries – is legally required regardless of the mother’s status.

Cash assistance: Through counties, the state helps about 230,000 children here legally even though the parents are not authorized to be in the U.S. The assistance is $345 for a child alone and is paid to the responsible adult, regardless of his or her eligibility. The cumulative cost to the state is $670 million.

Higher education:

Colleges do not collect “tens of millions of dollars” from students who do not have valid status. Those here illegally can qualify for lower in-state tuition – a big savings for them – if they can prove they have lived in California for three years and received a diploma from a high school in the state. That law has been upheld in court. However, they are not eligible for financial aid.