Jerry Brown was the kid the first time he was governor, nearly 40 years ago. Now he is definitely providing adult supervision in Sacramento.

Since retaking the executive suite, Brown has lectured Californians – and the Legislature – about the need to get real on the state budget. His stance is pretty simple: the state should not spend more than it takes in.

It took a while, but it looks as if Brown’s mantra has finally penetrated both the electorate and the political class.

Last year Brown persuaded the voters to raise taxes to help balance the budget and protect the schools from deep cuts. If you want the services, he said, you have to pay for them.

Now he has followed up by convincing fellow Democrats in the Legislature to leave billions of dollars unspent as a hedge against a downturn in the stock market, the economy or both.

The budget for the fiscal year that begins July 1 will be balanced with a modest reserve. But not even on the books will be about $3 billion in potential tax revenue that the Legislature’s non-partisan budget analyst says will materialize but which Brown’s advisers did not include in their projections.

The difference comes from how the analyst and Brown’s Department of Finance treat a recent spike in capital gains taxes paid by Californians whose investments have done well. The analyst says that even if the stock market is flat for the rest of this year, gains already booked will mean a gusher of new money for the state treasury. Privately, Brown might agree. But even if he does, he wants to keep the money off the table so legislators won’t spend it. The governor insists the difference is an honest disagreement.

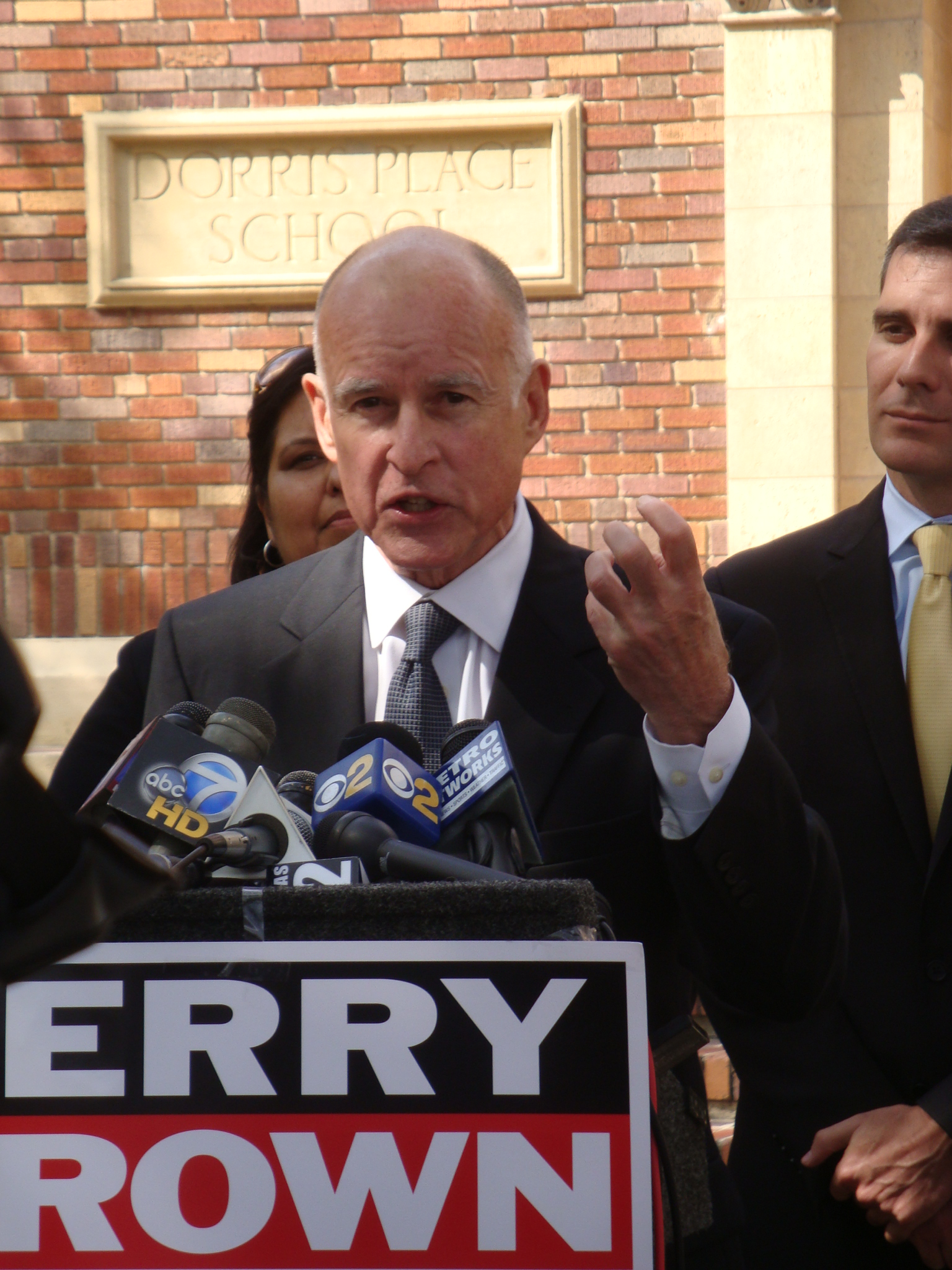

“We have had boom and bust,” Brown said as he and the legislative leaders announced their budget agreement, which largely reflected his priorities. “I’m trying to be a good, prudent steward of the people’s money…In general, I think prudence rather than exuberance should be the order of the day.”

Brown prevailed on the revenue issue, but in the end, legislators know that if they are right, it won’t matter much. If the money does come in as they hope, they can always spend it later this year or, at the latest, in the next budget. It’s not as if they are planning a tax cut, or even a rebate. But the delay was important to Brown. He didn’t want to add new spending that would have to be rolled back later.

“It’s the best of all worlds,” said Senate Leader Darrell Steinberg, a Democrat from Sacramento.

Brown also got most of what he was seeking on the big-ticket items in the budget – education and health care.

On education, he proposed and won approval for a fundamental shift in the way the state pays for the public schools. Instead of a basic grant per student and dozens of special programs designed in Sacramento, known as “categoricals,” Brown suggested a basic grant and then extra money directed at two types of students, low-income kids and immigrant children still struggling to learn English. Local school districts would largely be freed to decide for themselves show to spend that money.

Legislators pushed back at first, arguing that Brown’s plan did not guarantee that every district would be made whole for the losses in state funding suffered during the Great Recession. But in the end, after a few tweaks, they agreed to most of what he was proposing. The governor showed the ability to compromise on the details in order to save the vision he had in mind.

“We made a proposal and these legislative gentlemen refined it,” Brown said. “Through the process, stuff gets done. They are the experts on how you get the votes.”

On health care, the big issue was how to go about expanding the state Medi-Cal program for the poor, in line with the federal health reform taking effect Jan. 1. Brown and the Democrats in the Legislature agreed that the state should grant eligibility to anyone with an income below about $16,000 a year, including single, childless adults, who in the past have been excluded from state-subsidized care. But the sides differed on how to go about it.

Although the expansion will be paid for mostly with federal money, Brown insisted on reducing the amount the state gives to counties to reimburse them for caring for those who have no coverage. He argued that with most people now getting either insurance or state-paid care, the counties will have fewer people to worry about. But the counties and their defenders in Sacramento argued that no one really knows what will happen when the new programs roll out Jan. 1, so it was premature to start taking money back on the assumption that the counties wouldn’t need it.

“Despite the expansion we’ve proposed…there are still people that are uninsured that will still go to public hospitals and other county services to receive emergency health care,” said Assembly Speaker John Perez.

In the end, though, legislators agreed to force the counties to forfeit $300 million in the coming year. After that, the state would take back more money based on a detailed examination of exactly how much the counties are saving. As much as $1 billion a year will eventually be at stake.

Legislators did score one major victory on health care: they persuaded Brown to reinstate, starting next year, dental care for adults in the Medi-Cal program, which had been cut during the lean years. Many experts believe that the elimination of dental care, while saving money in the short term, actually cost the state more in emergency room costs and other health bills brought on by the lack of dental care.

Brown’s third budget since retaking the governor’s office isn’t perfect. While it pays down some debt, it creates more, especially with a thinly justified, $500 million loan to the general fund from the state program that charges fees to industry to help fight climate change. The budget also largely ignores a burgeoning deficit in the state teachers retirements fund and the projected cost of health care for retired state employees.

But the spending plan, in terms of balance, fairness and an eye toward the future, is Brown’s best so far. It is also the most prudent budget to come out of Sacramento in a decade.

Daniel Weintraub has covered public policy in California for 25 years. He is editor of the California Health Report at www.calhealthreport.org.