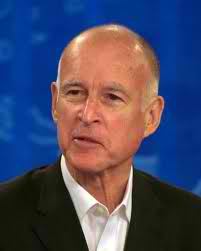

The state’s health and social safety net for its poorest residents would be slashed even if voters approve a tax increase that Gov. Jerry Brown proposes for the November ballot, Brown said Thursday as he released his spending blueprint for the coming year. And if the voters reject new taxes, he said, California’s schools and universities would go on the chopping block.

Brown’s budget includes deep cuts in welfare, Medi-Cal and home-based services for the disabled, which he wants to enact as soon as possible, and threatens a huge reduction to education – the equivalent of three weeks of classes — if voters reject a proposed increase in the sales tax and income tax in November.

“We are making some very painful reductions,” Brown told reporters at the Capitol.”This is not nice stuff, but that’s what it takes to balance the budget.

As part of this plan for the schools, Brown proposed giving local districts far more flexibility to spend their money the way they see fit, including the right to increase class sizes in the lower grades without losing money that had been targeted for keeping classes small. He said aside from some basic protections for civil rights, he did not believe it was wise for Sacramento to dictate policy to local communities. Residents of rural Kern or Modoc counties (whom he referred to as “Modocians”) might want to do things differently than those in San Francisco.

“Let a thousand flowers bloom,” Brown said, apparently quoting the late Chinese dictator Mao Tse-tung, although scholars say the Communist Party chairman actually referred to “one hundred flowers” in a speech encouraging intellectuals to criticize his regime. Many of those who spoke out were executed for their views.

Later, when asked why he was targeting kindergarten-through-community college education and the state’s public universities for cuts to be triggered if voters turn down his tax increase, Brown replied, “That’s where the money is.”

Brown added: “As Willie Sutton said, when asked why he robbed banks, he said, ‘that’s where the money is.’”

Sutton actually denied saying that infamous quote, pinning it instead on the imagination of a sensationalist newspaper reporter, but Brown made his point. He said the state simply does not have enough money to continue what he described as “generous” health and social service programs.

“The state of California’s government is a very generous, compassionate political jurisdiction,” Brown said. “When we have to reduce our spending, that spending is going to come from programs that are doing good, in schools, in health care, in all the other areas that constitute public service. Obviously that’s the only thing to cut. If there were more bad programs, or lower value programs, we’d cut those. We can’t spend what we don’t have. It’s not nice. We don’t like it. But the economy and the tax statutes of California make only so much money available. We have to spend it and make tough choices.”

Among the choices Brown proposed Thursday was a move to reduce from 48 months to 24 months the amount of time a person could remain on welfare unless they landed an unsubsidized job. This would mean ending aid to an estimated 270,000 adults, nearly half of the current caseload, for a savings of about $1.1 billion a year to the state. People who found work but were still eligible for aid could remain in the program for another two years.

Frank Mecca, director of the County Welfare Directors Association of California, described Brown’s proposal as “deeply troubling.”

“Children and families who are already living in poverty will struggle even more to have their basic food and housing needs met,” Mecca said. “Studies show children who fall into poverty during economic recessions are more likely to become adults plagued by poverty, earning less themselves, achieving lower levels of education, and reporting poorer health.”

Brown also proposed ending state-subsidized domestic services to disabled people who live with other non-disabled adults or minor children, on the theory that those people can take care of themselves. This would be on top of a 20 percent reduction in home care services triggered automatically this month when the state’s tax revenues fell short of projections. The latest proposal is expected to end services for a quarter-million people for a savings of about $168 million.

Brown also proposed moving more people in the state’s Medi-Cal program into managed care, a move he said would save more than $1 billion a year when fully implemented. And he suggested charging families who get their insurance through the Healthy Families program higher premiums while combining that program’s services with Medi-Cal.

State Senate Leader Darrell Steinberg said it would be a mistake for the Legislature to make the cuts Brown is suggesting early, because growing state revenues might make them unnecessary.

“We’re not going to make those cuts to Cal-Works and child care in March,” Steinberg said.