As surfers cruise on blue-green surf and seagulls perch on the soft sand, it’s hard to see Long Beach as anything other than a picturesque beach town, especially when it’s teaming with summer tourists. But some of the city’s 450,000 residents say that their environment is less than idyllic and that the air they breathe is making them sick.

Diesel fumes from the Port of Long Beach—one of the busiest in the nation—mingle with a constant stream of exhaust from the 710 and 405 freeways, hiking the region’s ozone smog and fine particulate matter levels, which pose serious health risks to residents.

Air quality in the Los Angeles-Long Beach area was rated among the worst in the American Lung Association’s 2010 State of the Air Report.

Poor air quality in this beachside city has translated into high rates of asthma. A chronic disease characterized by inflammation of a person’s air passages, asthma can temporarily narrow the airways that carry oxygen to the lungs. In Long Beach, 21.9% of children suffer from asthma, compared to 15.6% in Los Angeles and 14.2% in the U.S., several studies show. Low-income and minority residents are hardest hit.

But a closely connected network of local government agencies, medical clinics and community groups in Long Beach have been dogged in their efforts to identify and treat every person with asthma who may not have access to care. The Children’s Clinic and the Long Beach Health and Human Services Healthy Homes Program are ramping up existing efforts to provide needy residents access to health care providers. They are also offering asthma education and management techniques to low-income communities nearest to the port.

The Children’s Clinic was recently awarded a $825,000 grant from the Port of Long Beach as part of the port’s long-term effort to mitigate the effects of pollutants as well as reduce dangerous emissions generated by cargo ships, equipment, tugboats and trucks. The Port’s Clean Air Action Plan funds a wide-ranging number of approaches to improve health care and treatment for residents in certain high impact neighborhoods. The newly funded The Children’s Clinic’s “Bridge to Health” program is a time-tested collaboration between health educators, physicians, community health workers and families at six clinic sites around the city.

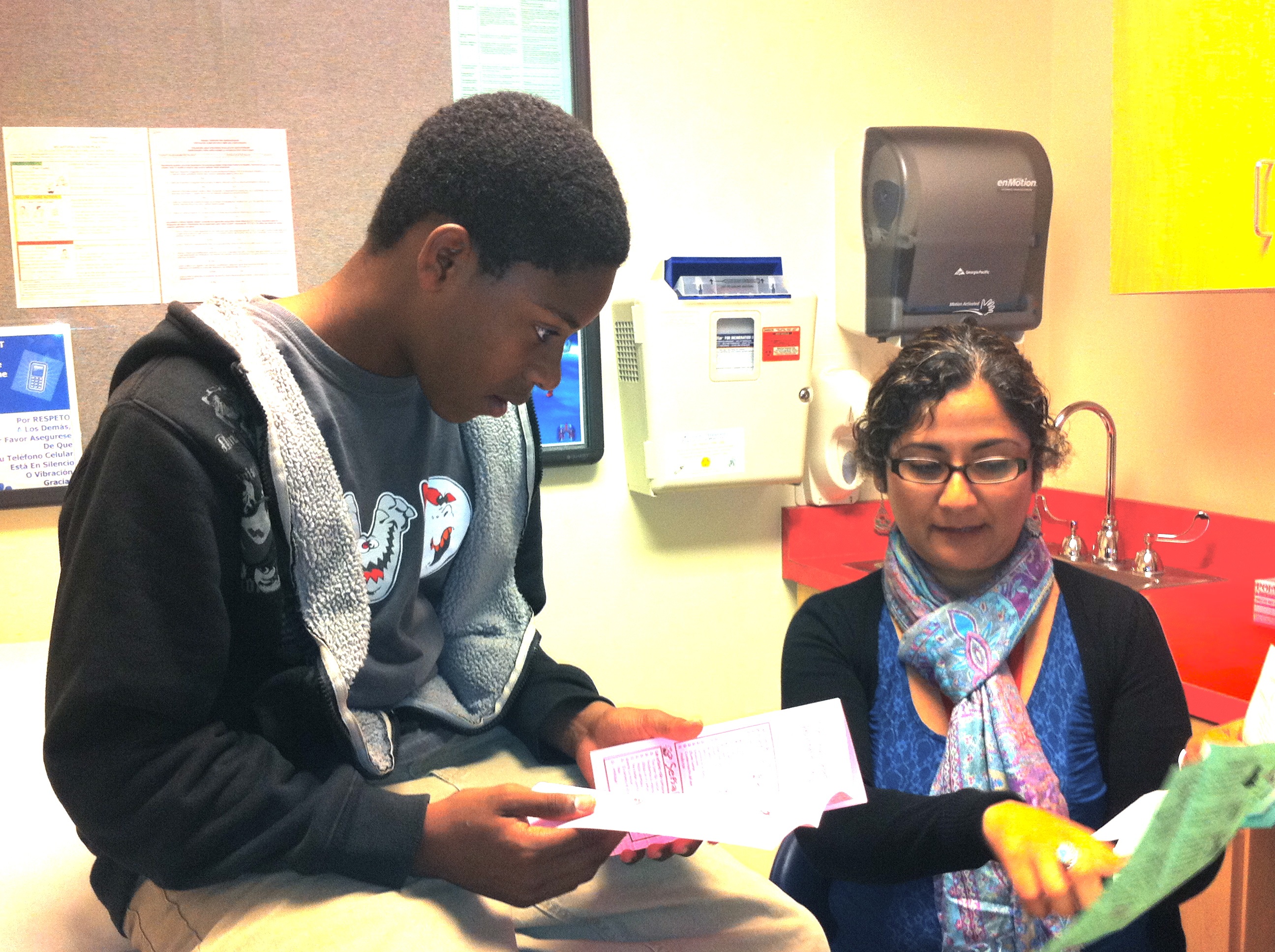

In a well-lit exam room at The Children’s Clinic one recent summer morning, Carolina Sanchez, the asthma coordinator, asks a genial, athletic 13-year-old to demonstrate how to use the peak flow meter, which measures how well someone can push air out of the lungs. Earnest Brandon Woodson White has had asthma since he was a baby. He carries an inhaler wherever he goes and sleeps with an air filter in his room. Brandon says that most of his friends at school have asthma, too. He loves sports, but often has to modulate how hard he runs or jumps on the basketball court.

“Now that I know how to control it, when I am wheezing, I just stop playing for a while or take a rest…that way it doesn’t hurt,” he says. His school is located near two freeways and the air feels heavy. “Sometimes you can smell it in air,” Brandon said. “It kind of sucks. I want to move the school somewhere else away from pollution.”

Sitting besides her son Brandon in the exam room, Rene Woodson says she’s grateful to the clinic for helping her son manage his illness. They provide his medicine for free and offer useful household tips, she says. One suggestion was to use non-toxic cleaners like Murphy’s Soap for instance, instead of a multi-purpose cleaner that can irritate the lungs with its a pungent odor.

“They are doing wonderful thing in my community,’’ said Woodson. “I feel comfortable coming here and asking questions and I’m so thankful for them for helping people in need.”

Sanchez, who has been at The Children’s Clinic for ten years, has helped hundreds of families like Woodson’s. However, many asthma suffers might never enter the clinic doors, so a group of community health workers canvass the neighborhood to find them.

The Long Beach Alliance for Children with Asthma (LBACA) is a partnership with private clinics that runs a community health worker home visiting program and an asthma resource center. They train doctors in asthma management and team up with schools, after-school programs, parks and recreational centers to develop asthma-friendly environments.

Dr. Elisa Nicholas, both the CEO of The Children’s Clinic and the Project Director of LBACA remembers when, during her medical training at Yale University, she saw a 6-year-old child with asthma die.

“Childhood asthma is treatable and it’s tragic when people die from it,” said Dr. Nicholas, a pediatrician. When she worked as a doctor in Kenya and Haiti, Dr. Nicholas was impressed at the power of the community health workers there to educate populations about managing chronic diseases. She saw how the same techniques could work serving low-income, minority residents in Long Beach who are disproportionately affected by asthma.

“We know it’s treatable,” she said, “We knew we could do better in our community.”

Whether the community health worker is from LBACA or The Children’s Clinic, a home visit generally involves a flip chart, a pile of pamphlets and a long talk. In her office at the clinic recently, Sanchez holds up the trusted educational tools she has used for years. When Sanchez knocks on the front door, the parent of the child—who may have been identified after a visit to one of the six clinic sites—is generally welcoming.

The first time she goes to a child’s home, she does an environmental assessment and looks for the presence of common triggers for asthma: Smoke, pets, mold, dust, cockroaches and other pollutants.

One of the educational charts she uses shows patients the signs of asthma in English and Spanish and also in clear illustrations. The brightly colored drawings show people experiencing chest tightness, shortness of breath, wheezing, and coughing. She always dispenses a “healthy homes kit” that includes a hypoallergenic shower curtain, pillowcase and bed liner. She suggests other simple lifestyle modifications: Opening the window when taking a shower can reduce mold and use cotton blankets instead of comforters, which are magnate for dust mites. Perfumes, plug-in air fresheners and strong candles can also trigger an attack. Home health workers will follow up with the doctors who have a variety of effective medications to help patients manage their symptoms. Inhalers with the medication albuterol can relieve symptoms almost immediately. There are many brands of maintenance drugs taken orally and steroids for emergencies. Once the patient has an action plan, the community health workers follow up with an asthma control test to make sure the patient is sticking to the program.

The Children’s Clinic and LBACA compliment similar work by the city’s health department, which is thwarting asthma’s grip on families in West Long Beach one house at a time through their healthy homes program. While The Children’s Clinic focuses on kids, the Community Asthma and Air Quality Resource Education Program targets adults. With a new, $1.5 million grant from the Port of Long Beach, CAARE is also ramping up patient enrollment.

All of these combined efforts have led to fewer missed days of school, less missed work, and fewer trips to the hospital for asthma patients. A recent report on the City of Long Beach’s efforts alone found that 32% fewer clients relied on emergency room care since 2008 and 20% of them reported missing one or more days of work during that period.

Kathy Estrada, public health educator for the city’s healthy homes program, says she has done countless visits to homes to help adults manage their asthma and conducted numerous workshops. But one mother’s story stuck. The woman had a child with asthma and vowed to make changes in her home. She attended four workshops and at the end of the last one told Estrada that her son’s asthma was finally under control.

“That was wonderful to hear,” Estrada said recently. “We want people to make minor changes in their home that can better their health.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.