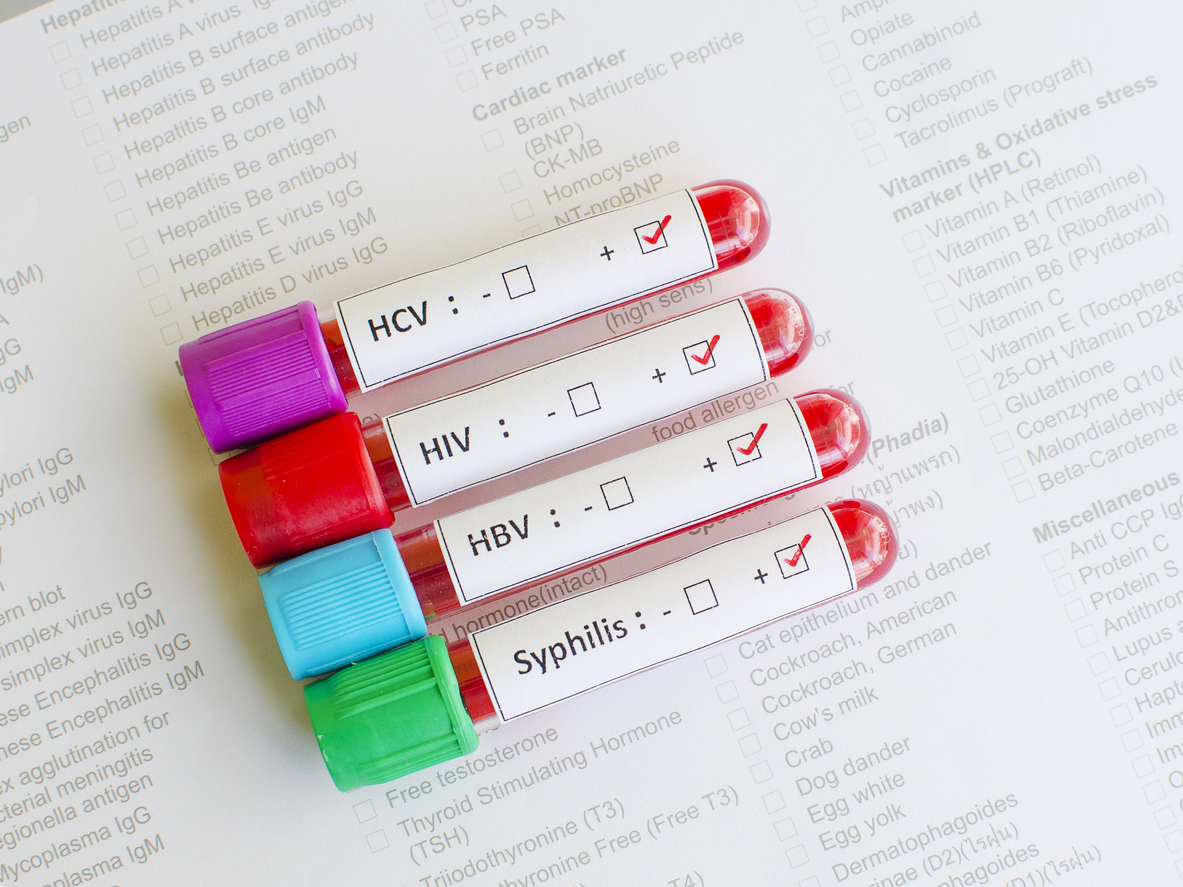

A coalition of 133 health-related groups in California are calling for $2 million from the governor and state legislature for a statewide task force to stamp out a mounting public health syndemic of HIV, hepatitis C and sexually transmitted diseases.

The proposed task force would pool health resources from around the state to set target dates to end the HIV, hepatitis C and STD epidemics. Among its goals: make comprehensive and culturally competent HIV, hepatitis C and STD prevention services more widely available and address social ills, such as poverty, stigma, and homelessness, that lie at the root of these epidemics.

The announcement follows a national initiative from the Trump Administration to wipe out HIV by 2030, a dramatic shift by an administration that proposed slashing domestic HIV/AIDs funding by $43 million.

California leads the nation in the number of new HIV diagnoses, the coalition noted in a nine-page consensus statement released last week. More than one in 10 of the 151,000 Californians with HIV — and most of the 400,000 Californians living with the viral infection hepatitis C — don’t know they’re infected.

The epidemics are intertwined with record rates of sexually transmitted diseases in the state, which disproportionately affect marginalized communities, including gay and bisexual men, transgender individuals and people of color. A statement from the coalition said Californians who are unknowingly infected with HIV, hepatitis C or STDs need better access to testing so they can seek treatment and avoid infecting others.

“Bold action is needed to integrate our response to these epidemics and eliminate health disparities and inequities,” the consensus statement reads. “With highly effective treatments and proven prevention tools, California can now dramatically reduce new transmissions, improve the health of people living with these conditions, and bring these epidemics to an end.”

Hepatitis C is curable, as are most STDs. The HIV prevention medication Truvada is up to 92 percent effective in stopping the spread of HIV among high-risk people when taken daily.

Between 2012 and 2016, the number of new HIV diagnoses in the state slid 2.8 percent, but white Californians benefited more from this decline than people of color. The rate of new HIV diagnosis among Hispanic individuals in 2016 was more than 50 percent higher than the rate of whites, while Black individuals’ HIV diagnosis rates were almost five times that of whites.

Since HIV afflicts many of the same populations as hepatitis C and STDs, the state needs a cohesive approach to stave off new infections in these communities, said Loris A. Mattox, executive director of the HIV Education and Prevention Project of Alameda County, one of the organizations in the coalition.

“We put things in silos. There’s the HIV prevention group, there’s the hep C prevention group, there’s the STD prevention group,” Mattox said. “We need to be more integrated, at the table, so we can combat it jointly. Separate doesn’t work.”

The state budget divides spending between HIV and STDs. In 2018-19, $23 million went to HIV prevention and $7.1 million to preventing STDs, according to the California Department of Public Health. While only $307,500 of STD monies went to viral hepatitis prevention, SB 75 authorized an additional $2.2 million for a three-year pilot program for hepatitis C screening and care.

It’s unclear whether Governor Newsom supports spending $2 million on a new task force. Spokesman Jesse Melgar said the governor “recognizes the importance of fighting to reduce, and ultimately eliminate, the HIV, hepatitis C and sexually transmitted infection epidemics” and “looks forward to working on these issues.”

The task force approach appears to be working in New York. After Governor Andrew Cuomo established a task force in 2014 with the goal of getting to just 750 new statewide HIV diagnosis by 2020, HIV diagnoses dropped nine percent in just one year. Last year, Cuomo set aside $5 million for a similar strategy for hepatitis C.

California already has dual plans to combat HIV and hepatitis C — Laying a Foundation for Getting to Zero: An Integrated HIV Surveillance, Prevention, and Care Plan and California Viral Hepatitis Prevention Strategic Plan, 2016-2020. The plans were developed through a collaboration among a wide array of state, local and community health partners, according to the California Department of Health.

Jason Reinking, who operated a mobile health unit for three years and now is medical director of an Oakland clinic for the homeless, supports a more coordinated strategy. He said co-located health services, such as mobile medical care and shower programs, are connecting people-in-need to HIV and hepatitis C screening and treatment — and could be replicated for STD screening and treatment too. But the programs often don’t share information and lack the means to reach the thousands of people sleeping on Oakland’s streets.

“One of the things holding back programs at the street level is making it financially sustainable,” Reinking said. “I think if there was more robust funding for these programs, we could focus more on care in the field and less on the funding.”