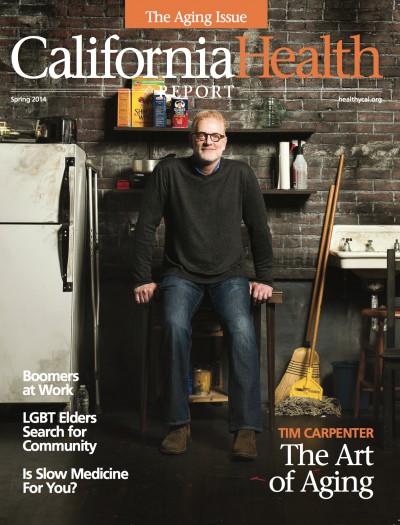

As a cub reporter for San Francisco’s alternative weekly fresh out of college in the early ’80s, Tim Carpenter loved slaying sacred cows. If asked what he was rebelling against during this “fun time,” he would have channeled Marlon Brando in “The Wild One” with this famous line: “Whaddaya got?”

Thankfully, some people never grow up. Carpenter, now 52, has directed his rebellious spirit into fixing a broken system—housing for the aging.

He found his way into health care after a move to Los Angeles. Initially, he wrote advertising copy for various health-care firms. Then, turning to management, he created a series of successful geriatric centers to help hospitals manage their complex older adult patients. Yet the never-ending cycle of sick- ness and treatment that he saw at the hospitals wore him down. Every day, he witnessed the workings of a fractured system, one that not only failed to keep older adults healthy and happy, but also was deeply resistant to change.

At 35 and seeking long-term solutions, he turned his sights specifically on senior housing, which in his experience seemed more like human ware- housing, punctuated by bingo games. With an introduction made by his wife, he found himself surveying senior housing projects with developer John Huskey.

During the tour, Carpenter peppered the developer with questions: “If there are so many cars in the parking lot, why don’t we see more people inside?”“What are the residents doing in their rooms?” “Why is your beautiful club room empty?”

Huskey knew Carpenter was on to something. And Huskey needed a new angle in a tough business. At a cross- roads himself, Huskey was hoping to make a bigger name for himself in a competitive California housing market. So he kept listening.

The duo spent months visiting facilities, surveying activities, quizzing site managers and asking endless questions of residents. Through it all, Carpenter pushed Huskey for an answer to this simple question: “Why are older adults hidden away in their rooms?” Huskey didn’t know. Carpenter told him he needed to know.

“There weren’t a lot of good reasons,” admits Huskey today. “Just a lot of alcoholism or people sitting in their rooms taking mind-numbing drugs.”

Carpenter then had his breakthrough idea. “I’m going to teach a writing class.” Huskey couldn’t believe it. “That’s the dumbest idea I’ve ever heard,” he replied.

Through Art, life

Huskey was in for a surprise: The class, held in one of Huskey’s senior housing facilities, was a huge success. Carpenter pushed the four students to write honestly about their lives. After they turned in an assignment that described an annoying person from their past, Carpenter challenged his elder scribes to contact their real-life antagonists.

They did. Most found it a healing experience. One was still hopping mad. Yet all the burgeoning authors were newly enthusiastic about the power of writing. The class blossomed into a roomful of excited, engaged older adults.

Then Huskey got another shock. The success of that class spread into the community. By gaining a reputation for active and engaging programming, Hus- key’s senior housing project—once just 90 percent occupied—filled up completely in just a few short months. And that last 10 percent was significant. “All the profit in multi-occupancy [housing] is between 90 percent and 96 percent,” says Huskey.

Carpenter has since built on the success of that class. Today, his nonprofit company, EngAGE, offers robust arts and exercise programming to 7,000 older Southern California adults in 34 senior living communities—22 of them Huskey sites.

Three exemplary EngAGE facilities— all in the Los Angeles area—serve as “artists colonies.” Their classes read like the catalog from a health-conscious arts school: acting for television and film, chorus, drum circle, yoga, anti-aging exercise, poetry in motion and short- film making. There are also a variety of lectures, musical performances, writing groups and healthy living classes. Carpenter says no matter the location or name of the site, his focus is the same: creative arts, exercise and wellness. In short, lifelong learning.

What began as a“dumb idea” became a golden calf: a housing model that served the needs of older adults—and was profitable. Largely due to Carpenter’s foresight, Huskey’s firm Meta Housing Corp. is now recognized as one of the most innovative developers in California. Its Long Beach Senior Arts Colony won several awards after open- ing in 2013, including a national Best New Development: Seniors-Active Adult from the trade publication Multi- Housing News.

“Tim’s been my Jiminy Cricket,” says Huskey. “He’s awakened in me more than just building senior housing.”

Learned Optimism

Underpinning the success of these housing communities are philosophies universal to all of Carpenter’s programs: Aging can be like college, with unlimited potential to experiment and reinvent yourself.

Carpenter’s own history made him a firm believer in reinvention and cultivating a spirit that spurs experimentation and risk taking—even in the face of life’s obstacles.

In his early 30s, Carpenter was living the gilded life of a bachelor in San Diego when a roommate returned from Palm Springs and pulled him aside. “I met this girl that you have to go out with. ”Nancy was friendly, beautiful and tall—Carpenter is 6 feet 3 inches—and a stage actress with a great interest in the arts. “She was very alive and soulful,” says Carpenter. Less than four months after they met, they were married.

Seven years later, daughter Zoe was born. But not long after the birth, Nancy was diagnosed with fibromyalgia and lupus. After seven more years and end- less doctor visits, Nancy succumbed to the H1N1 virus (swine flu) while the three were on vacation in Australia. She was just 48.

Nancy’s death was not all that Carpenter had faced. Starting in his 20s, he suffered the death of both parents and a brother. Of the four loved ones, three died in his arms. Perhaps because of these losses, Carpenter continues to count on the very trait he asks older adults to embrace: “learned optimism.”

For Carpenter, stimulating the mind, body and spirit are the doorways to learned optimism. “People connect optimism with larger, big picture stuff,” he says. And the arts are a key to this stimulation.

Life is not a spectator sport, he insists. The responsibility for a happy, engaged life is yours. In a world where good health is often heaved onto the shoulders of others—particularly physicians— Carpenter brings it back home. He summarizes the EngAGE philosophy this way: “We expect you to come here to play.”

Sally Connors is a perfect example. At first, she objected when her daughter brought her to the Burbank site. “It says ‘Burbank Senior Arts Colony,’” recalls Connors. “But I’m not an artist.” “But you could be,” replied her daughter. For Connors, the move was life changing. She had permission to play and experiment. “I joined everything,” she says. “I went to every class they offered. And still do.”

Besides taking painting, filmmaking and writing of all kinds—plays, poetry

and screenplays—Connors has found her home as an actress. She remembers her first tentative line delivered on stage. “People laughed,” she recalls. “And I was just blown away. They found something I said was funny. And a star was born.”

Getting sedentary older adults to participate in classes is sometimes a huge challenge. So Carpenter and his staff have devised several innovative solutions. “We [use] really skilled, high-level teachers who have big personalities and who are willing to talk to people and knock on doors,” he says. Residents are typically first prodded to join gardening classes or intergenerational programs alongside children. “Many of our residents who come into senior communities thinking it’s a necessary evil find themselves instead,” he says.

Carpenter credits his knack for big picture thinking to his years as a journalist and writer. After college, he wrote constantly: short stories, plays, poetry and screenplays. He even got an agent in Los Angeles. A rare mix of businessman and artist, he seemed ideally suited for creative solutions that fulfilled a bottom line. “It takes time for this type of programming to reap financial reward, but it does,” he says, citing lower turnover in senior housing and reduced marketing costs needed to at- tract potential residents.

Despite his success, not everyone understands what Carpenter does.

“When some [developers] are looking at coffee on the cost chart, you figure tai chi isn’t going to make the cut,” he laughs. EngAGE programs have not been renewed at some facilities because of similar cost-cutting measures.

Today, Carpenter is busier than ever. Besides raising funds from corporations and foundations to support the non- profit EngAGE, he supervises planned expansions into Portland, Minneapolis and the Raleigh-Durham, N.C., area.

He’s received plenty of kudos for his work. In 2011, he delivered the TEDxSo- Cal talk “Thriving As We Age.” That same year, he received a leadership award from the James Irvine Foundation. He’s also a fellow at Ashoka, which supports global social change.

Carpenter co-hosts the weekly radio show “Experience Talks” recorded at L.A.’s progressive station KPFK-FM. He has interviewed luminaries like actor Tony Curtis, who gave what became his final interview.

Although the communities EngAGE supports are successful, Carpenter is di- vided about the success of similar sites. Affordable housing projects depend on government subsidies to supplement their costs and bring down rents. “It’s very difficult to build affordable housing without some government subsidy to fill the gap,” he says. He points to the elimination of more than 400 California redevelopment agencies two years ago as part of Governor Jerry’s Brown’s budget cuts as a source of the problem. Dwindling retirement savings are also a huge concern for people in their older years.

He says the United States needs more programs like the Osher Lifelong

Learning Institutes, along with wellness programs and creative arts programs targeting older adults. And governments large and small need to focus on being more “age-friendly.” “Cities have to make this a higher priority,” he says.

Still, Carpenter remains doggedly optimistic about the future.

Research supports the importance of lifelong learning and social engagement. The oft-cited MacArthur Foundation

Research Network on an Aging Society asserts that social activity is equally important to heredity when it comes to longevity. “You can have a significant impact on your health, both physical and mental, in how you live it,” says Carpenter.

Huskey has no doubt Carpenter will continue to have the same influence on others. “Tim changes people’s lives every day.”

This story originally appeared in the California Health Report magazine. Subscribe here for the free quarterly.