At Kendall Hollinger’s school, the classroom and cafeteria are adjacent, and there are no students slamming locker doors and yelling “Wait up!” to a group of friends. That’s because the 17-year-old has been home-hospital schooled since kindergarten, owing to severe and potentially deadly allergies.

The trouble started when she was only two days old, after a toxic reaction to her mother’s milk caused her to stop breathing. Later, doctors determined that Kendall was allergic to 95 percent of all foods, including eggs, soy and pork. Luckily, she can eat a number of meats, potatoes, rice and chocolate, the latter being her favorite. But she’s allergic to seeds and nuts; just a whiff could send her into deadly anaphylactic shock.

At 3, she had to be fitted with a feeding tube so meals could be poured directly into her stomach, so she can get all her nutrition needs met. Her education had to be adapted to suit her, as well.

“I wanted Kenny to go to public school,” her mother, Kim Hollinger said, calling her daughter by her nickname. “Tim and I went through public school, and that was our plan.” They envisioned Kendall ambling down the street with friends, toting a backpack like a tortoise shell, en route to school in their Southern California neighborhood. But Kendall’s doctors told the Hollingers that it simply wasn’t safe. That became abundantly clear the first time Kim went to see the school nurse to discuss Kendall’s situation, and the nurse listened while munching a handful of nuts.

Home hospital schooling (HHS) was part of a bill passed by the California State Assembly nearly 30 years ago, ensuring that students didn’t fall behind when it became impossible or ill advised for them to attend school, said Jacie Ragland, program consultant at the California Department of Education in Sacramento.

“Circumstances vary,” she said, adding, “Sometimes a student may have cancer, a broken leg; they may have anxiety or depression.” HHS makes sure the child doesn’t fall behind and be put “at an academic disadvantage,” said Ragland. So the teacher comes to the student until the crisis has passed.

Patients at the Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital in Palo Alto, CA, may be so ill that they’re never in a position to go (or go back) to a conventional school, so they attend one located within the hospital. The child could be dealing with a brain tumor, recovering from a heart transplant or battling cystic fibrosis. Students include in-patients, out-patients and, under certain circumstances, community members who fall into the K-12 age range. Four teachers, three aids and lots of volunteers do some instruction in the classroom, and some at bedside.

The school falls within the Palo Alto Unified School District, where even the most ill patients can crave the normality of a school day, however modified. “They feel more agitated by not going to school and not doing homework,” said Kathy Ho, one of the high school teachers. The 90-year-old educational program, started in 1924, holds a prom for all grades at the end of the year, said Ho, so no one has to miss out because they’re in the hospital.

The Hollingers had high hopes that Kendall would enjoy all the traditional rites of passage that come during the school years, but potential risks to her health never abated. (For example, she used to love pizza, until she acquired an allergy to tomatoes.)

“We could not create an environment that was safe,” Kim said. “Her list of allergens is too long, and it would be unrealistic on our part” to ask the other kids to accommodate her. But finding the right teacher to come to their home was not easy. They went through a few who didn’t mesh well, and then got lucky. Jane Gordon-Topper has been one of Kendall’s teachers the last dozen years, and they’ve formed a strong bond. Kendall has her for English and history.

“I only thought it was going to be one year and it’s been 12,” said Gordon-Topper. “I teach kindergarten, but I’m credentialed to teach students through 18.” Another teacher covers math and science, while a third gives her guitar lessons, Kendall’s one elective.

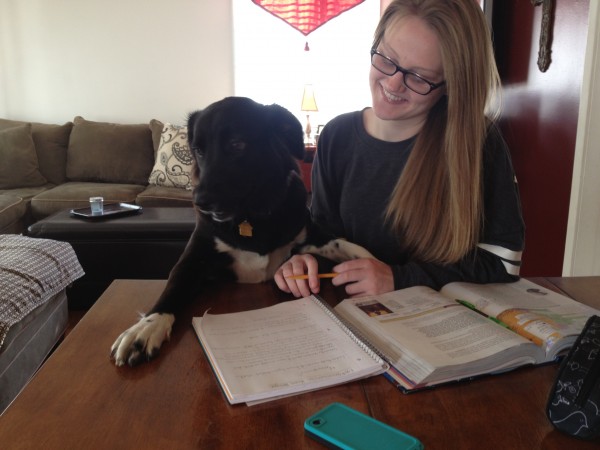

There are good and bad aspects to HHS, Kendall finds: “It’s not 30 other students asking a question. So you can ask the one question that you have, and the teachers are good about going at my pace.” But you can’t get away with the usual kid stuff. “No texting under the table and no not turning in your homework, because my mother sees everything,” said Kendall. Kim is often nearby during Kendall’s seven- and-a-half hours of instruction each week.

Kendall is also a championship skater, with a dresser top full of trophies. At church, the budding singer/songwriter helps lead the music ministry. These activities help serve as social outlets. She imagines that if she went to a conventional school, she would “fit in with the band geeks or theater kids.” Once she went to a girlfriend’s school dance when the latter’s date fell through. “I was a wallflower for a while, and kind of shy,” Kendall recalled.

Sometimes she’s reminded of her situation by a question on a test, such as this one that started out: “If you were running for an office at school…” Kendall thought: What am I going to do, Ask Lola?

Lola is her border collie/black Labrador Retriever—a Borador—whom Kendall has had since the dog was a few weeks old. Roughly a year ago, Lola and her sister, Gracie, were among a handful of pups rescued from a Southern California crack house, where several of their siblings had drowned or starved.

At first the Hollingers were just going to foster Lola, but Kendall lobbied to keep her as a service dog. And they were off to a promising start because the teen wasn’t allergic to her.

Kendall leveraged the Lola deal by suggesting that the little ball of fluff could grow up to be a peanut-sniffing dog, alerting her mistress when dangerous nuts might be too close for comfort—a legitimate job currently performed by trained service animals.

Lola recently alerted Kendall that peanuts were being served at a fast-food place during a Hollinger family outing to the mall, and they quickly diverted in a different direction. In another year, Lola may help Kendall forge a brave new frontier: College. Letters of interest from universities have already begun to arrive.

Kendall plans to stick to a college close to home the first two years, and then venture out into that great big world for her final two years. Baylor University in a Texas might get a look. “There’s going to be a lot less stress because of Lola,” said Kendall. “I’m excited that she’s coming with me.”