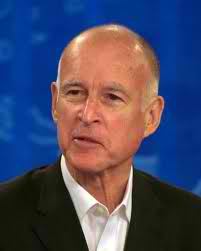

Gov. Jerry Brown and his fellow Democrats in the state Legislature are headed for a showdown over the way California pays for its public schools.

Brown is proposing a revolutionary plan to give extra state aid to schools that teach large numbers of poor and immigrant children. But he is getting pushback from some in the Legislature who think his plan goes too far – at the expense of the general-purpose money that every school district receives.

Brown argues that few things are more urgent than the need to improve schooling for California’s most vulnerable children, which would improve their lives, lower social welfare costs and boost the economy. Characterizing his idea as part of a civil rights battle, Brown last month said opponents are in for “the fight of their lives” if they think they are going to block his plan.

“I’m not going to give up until the last hour, and I’m going to fight with everything I have, and whatever we have to bring to bear in this battle, we’re bringing it,” Brown said.

The governor has the public on his side. Polls show voters like the idea of focusing state resources on students from low-income families. A recent poll by the Public Policy Institute of California, for example, found that two-thirds of Californians think schools with more low-income students should receive more state funding.

But critics of Brown’s plan say that several years of budget cuts have left all schools so short of resources that it would be unfair to divert money from mainstream programs until everyone catches up. Brown’s formula, critics say, would hurt students in suburban districts that have relatively low enrollments of poor and immigrant students. Even the needy students in relatively affluent districts would be shortchanged by Brown’s plan, some legislators say.

The governor, though, is determined to seize a rare opportunity for radical reform arising out of the state’s slow but steady economic recovery and the tax increase voters approved at the ballot box last November. Tax revenues are rising again, and a state constitutional provision requires the Legislature and the governor to set aside much of that new money for schools.

Public school enrollment, meanwhile, is flat or even shrinking, thanks to the state’s changing demographics. That means that the amount of money per student California spends on education is almost certainly going to be rising in the years ahead.

Rather than spreading that money around the way it’s always been done, Brown proposes a fundamental shift. He wants to give every school district a basic grant per student, then add 35 percent more per child for each student who is either low-income or learning English as a second language.

On top of that, districts with more than half their enrollment made up of low-income students or “English learners” would get another bump of 35 percent per student to deal with the challenges of educating high concentrations of disadvantaged pupils.

Under Brown’s plan, no district would get less than it received last year, and eventually, every district would get back to the per-student funding they had before the recession. But the growth rate would be faster for districts with high numbers of poor and immigrant children.

To show how this would play out over time, Brown’s Department of Finance recently released projections showing how much every school district in the state would get under his plan compared to the status quo. The numbers include only the state money that would be affected by Brown’s proposal, which excludes restricted funds such as paying for special education, federal funds and locally raised revenues such as parcel taxes.

Consider the schools in Santa Ana and San Juan Capistrano.

Today, Santa Ana Unified gets about $400 more per student than Capistrano, but 78 percent of Santa Ana’s students are poor and more than half are English learners, while in Capistrano, 23 percent are low-income and just 10 percent are still learning English.

Under the status quo, according to Brown’s numbers, that modest funding gap would pretty much remain through the rest of the decade, with Santa Ana getting $10,135 per student in 2019-2020 and Capistrano receiving $9,875.

But under Brown’s plan, Santa Ana would do much better, eventually qualifying for $11,804 per student, while Capistrano would get $8,964 per child. Capistrano’s funding would still increase by nearly 50 percent during this period. But Santa Ana’s would climb by 84 percent.

Brown’s plan would require school districts getting the bonus to spend that extra money on low-income children and English learners, but they would have tremendous flexibility in how they did that. They could hire more tutors, teachers’ aides, or translators. They could buy enrichment materials or computers, or extend the school day or the school year for certain students. Those decisions would be up to each district.

Democrats in the Legislature say they agree with Brown that poor and immigrant students should get more resources. Just not as much as he suggests.

One proposal backed by Senate leader Darrell Steinberg would eliminate the extra 35 percent bump Brown proposes for the most heavily impacted districts, which the governor calls a “concentration” grant. Instead, half of that money would go to general aid, distributed statewide on a per pupil basis. The other half would go toward increasing the per-student bonus Brown proposes for the targeted children.

Overall, that would mean less growth in the budgets for heavily impacted districts like Santa Ana. But it would mean a bit more money for districts where low-income and immigrant kids make up a substantial share of the enrollment yet fall short of a majority.

Given Brown’s commitment to this issue, it seems likely that some form of his plan will make it through the Legislature this year. His allies are starting to put pressure on Democratic lawmakers to go along. And an unexpected surge in tax receipts this year might help smooth the way by providing enough money to ease the fears of the districts that would be relative losers under Brown’s proposal.

One way or another, parents, teachers and anyone with a stake in public education should be prepared for some big changes ahead.

Daniel Weintraub has been covering public policy in California for 25 years. He is editor of the California Health Report at www.calhealthreport.org