By Jenn Walker

Sacramento freeways are notorious for traffic during rush hour. Not only is the capitol region flanked by two major rivers, cutting off potential access routes in and out of the area, but its suburbs are expanding at a rapid rate. But help may soon be on the way.

Sacramento’s metropolitan planning organization, the Sacramento Area Council of Governments, or SACOG, unanimously adopted a 313-page, $35 billion transportation and development plan last week to remedy such issues within the six-county region.

The council must produce a transportation plan every four years. However, the Metropolitan Transportation Plan/Sustainable Communities Strategy for 2035 is the first to include a Sustainable Communities Strategy in adherence to Senate Bill 375, legislation that seeks to integrate transportation planning with the state’s goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

A key feature of the plan is promoting mixed-use neighborhoods, locating shopping centers, homes, schools and jobs close together. The assumption is that closer proximity decreases travel time in the car, or the need to use a car altogether, resulting in less vehicle emissions and better air quality.

As obvious as this may seem, planners have advised the exact opposite in the last 60-plus years, McKeever says.

In 2010, the California Air Resources Board set greenhouse gas reduction targets for the Sacramento region that require a nine percent per capita reduction by 2020 and 16 percent per capita reduction by 2035. The plan is expected to meet these air quality standards.

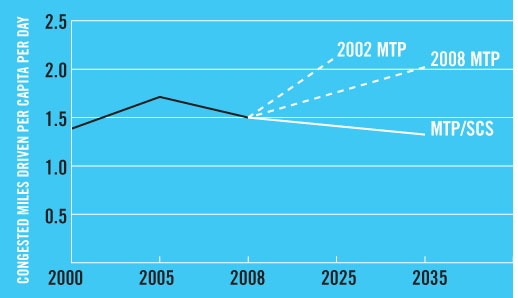

With more alternatives to driving, this should also lower the number of cars on the road.

“Most people say sitting in heavy congestion is the lowest, most hated human activity that they have to experience,” McKeever says. “So we think that there is a quality of life benefit, as well as an economic and air quality benefit, to just giving people back more time in their daily life to presumably spend time at home with their families, or recreate in some way that’s more pleasurable than sitting in your car.”

According to the plan, the area’s current population of 2.3 million will increase by roughly 39 percent in the next 23 years, and the number of commuters in the area will increase more than threefold.

To help absorb that increase, the plan allocates about $7.4 billion to widen roads and create additional river crossings.

Currently, downtown Sacramento is difficult to access, enclosed by the Sacramento River to the west and the American River to the north. To increase accessibility, the plan proposes three new bridges. Two bridges will cross the Sacramento River and one will cross the American River, creating three more entries and exits in and out of the area.

The plan allots another $11.5 billion to maintain the region’s 22,000 lane miles of existing streets and 5,000-plus lane miles of freeways and expressways. As McKeever explains, the plan applies the fix-it-first approach whenever possible.

Some transportation improvements mean simply providing connections between two places. Currently, a 60-acre infill project is separated from Sacramento City College by seven major rail tracks. The plan proposes building a pedestrian bridge over the tracks to connect the neighborhood to the college.

Poor connectivity is a common problem in the region’s transit system, McKeever says.

“It’s literally thousands of little tiny investments like that, that when you add them all up, suddenly you’ve made transit far more convenient for people without them having to move their house or move the train station,” he says. “You’ve just made it easier for them to actually get to the train station.”

Approximately $2.8 billion will apply to bicycle and pedestrian improvements like these, in addition to about a $600 million chunk of the road and rehabilitation budget.

The plan also proposes increasing transit service to 15-minute or less intervals in higher density areas, and increasing transit service hours by 42 percent per capita.

The Coalition on Regional Equity, a partnership of local organizations focused on promoting equity in the Sacramento region, applauded the plan as a step in the right direction in a public comment letter late last year.

It suggested, however, that the plan do more to meet transportation needs of vulnerable populations, namely low income groups, communities of color and people 18 and under, by lowering fares, discounting monthly passes, and providing transit routes that accommodate night shift workers. It also suggested that transit networks provide enough connectivity so that people can access everyday needs without requiring a car, especially for those who are transit-dependent.

Seniors, who inevitably become transit-dependent, are often forgotten about in these plans, says Barbara Stanton, coalition affiliate and founder and director of the transit advocacy group Ridership for the Masses.

What are the alternatives to getting to a bus station when a senior’s license gets taken away, she asks. Walking or riding a bike is not typically an option.

“Then, all of a sudden, you just don’t have access, and I think it’s a panic type of situation,” she says. “Are you going to be able to not have to walk a third of a mile [or] a quarter of a mile to get a bus if you are a senior?”

The plan also implements the Rural Urban Connection Strategy, which focuses on preserving and maintaining the health and profitability of the region’s agricultural sector. It is expected to reduce the acres of farmland affected by development from 333 acres per 1,000 residents to 42 acres per 1,000 residents.

“[SACOG] has done absolutely tremendous work on the needs of the agricultural community and demonstrating the benefits of preserving our agricultural base,” says Matthew Baker, habitat director of the Environmental Council of Sacramento.

Yet an equally sophisticated analysis needs to be applied to development effects on surrounding habitats and ecosystems, he says. Quality data on how development will affect nearby habitats is lacking, he explains, and they are essential to providing people natural spaces for education and recreation.

Overall, Baker says that SACOG has been attentive to the suggestions of the environmental and health community, and that it is already making moves to address these issues.

“I really think that’s one of the success stories of this plan, is the incredible job and responsiveness SACOG has displayed with the public and their engagement with experts in these areas,” he says.

The greatest challenge, he adds, will be local compliance with this regional plan.

“The [plan] is simply a planning tool and has no regulatory authority,” he says. “We really fear that on the ground, local jurisdictions are continuing to move with the boom year status quo, or [are] hoping to, and we feel that would be a detriment to this plan that SACOG has put together.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.