South Los Angeles twenty years after the riots

By Robert Fulton

California Health Report

On April 29, 1992, Cary Earle worked on his yet-unopened restaurant on Crenshaw Boulevard in the South Los Angeles neighborhood of the same name. Cary and his brother Duane had operated hot dog carts in L.A. for nearly a decade, and after years of work were able to establish a permanent location where they could serve hot dogs, burgers and fries.

Because the new Earlez Grille had yet to open, there was little of value on site. No cash, no equipment. Just Cary Earle and some cohorts working to get the restaurant ready for its upcoming opening.

That opening would be delayed.

Los Angeles exploded that day, following the acquittal of four white police officers charged in the beating of African American motorist Rodney King.

This month marks the 20th anniversary of the 1992 Los Angeles Riots. And according to residents and community leaders in South Los Angeles, too little has changed over the past two decades.

Like many around the region and the nation, Cary watched the violence unfold on television.

“The air became a little thick,” Earle said. “You felt a little tension.”

A few doors down from the restaurant, a liquor store went up in flames. Then a stationary store. Earle called the Los Angeles Fire Department, but emergency calls stretched the fire department thin, as looters and arsonists set hundreds of fires during the six days of unrest.

Cary and his crew sprayed down the building with a water hose. The structure caught fire, but the fire department arrived and suppressed the flames. Earlez suffered significant damage, but the restaurant was saved and opened a few months later.

“It only takes one person,” said Earle, now 49, sitting in the most recent iteration of Earlez Grille, at the corner of Crenshaw Boulevard and Exposition Drive. “It was a chain reaction. Most of the people that started the problems were not people from the community. Most of these people were passing through. There’s a lot of good people that live down here. In between those knuckleheads, there’s a lot of good people.”

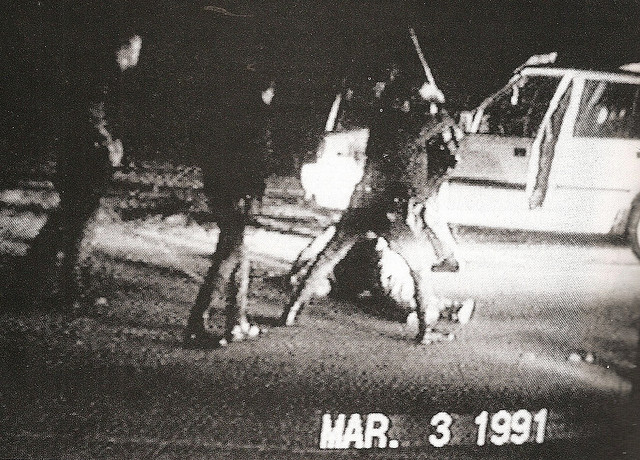

On March 3, 1991, George Holliday filmed members of the Los Angeles police department beating Rodney King on the side of the road following a traffic stop. The Los Angeles District Attorney charged Stacey Koon, Laurence Powell, Timothy Wind and Theodore Briseno with assault, and a jury in Simi Valley acquitted the four officers.

The unrest that followed resulted in 53 deaths, hundreds more injured and an estimated one billion dollars in damage. The riots originated in South L.A., but the unrest soon spread to other parts of the city and region. Mayor Tom Bradley imposed a curfew, and the National Guard was called in. The mayor did not lift the curfew until May 4.

“It was the most unjustifiable thing you can ever see,” Earle said. “You’re burning your own neighborhood.”

Discussing the events of 1992 can lead to a semantics debate. The word “riot” is common. Some prefer “uprising,” “rebellion” or “civil unrest.”

Reverend Cecil “Chip” Murray prefers the latter, but also applies “explosion,” citing the Langston Hughes poem “A Dream Deferred”:

“What happens to a dream deferred?/Does it dry up/like a raisin in the sun?/Or fester like a sore–/And then run?/Does it stink like rotten meat?/Or crust and sugar over–/like a syrupy sweet?/Maybe it just sags/like a heavy load/Or does it explode?”

“I certainly am not offended by the use of the other terms, but I think the civil unrest explains more completely a dream that exploded,” Murray said.

Rev. Murray was the pastor at the First African Methodist Episcopal Church in South Los Angeles for 27 years, and is now the John R. Tansey Chair of Christian Ethics in the USC School of Religion. He is also the Chairman of USC’s recently opened Cecil Murray Center for Community Engagement, which works to empower the undeserved community through job placement, mentoring, reentry programs for released prisoners, housing and more.

As pastor at FAME, Rev. Murray worked to keep the peace in 1992. He still sees many of the same inequities in the area, including poverty, lack of jobs, under performing schools, and a biased penal system.

“If history does in fact repeat itself, the only fix must be to change our way of operation,” said Murray, 82, sitting in the center that bares his name, located a few blocks east of the USC campus, tucked up against the 110 Freeway. “To keep on doing the same old thing in the same old way and to expect different results, I think that’s the definition they say of insanity.”

According to the website city-data.com, the poverty rate in zip codes in South Los Angeles is greater than 30 percent. That rate is 15.1 in the nation and 19.5 in Los Angeles as a whole, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

The life expectancy in the Florence-Graham neighborhood east of the 110 is 76.7 years, according to the Los Angeles County Department of Health. The county average is 80.3, and according to the Centers of Disease Control, the national average is 77.9.

John Griffith, PhD., cites a need for access to housing and jobs in South L.A. Dr. Griffith is the president and CEO of Kedren Community Health Center, which provides mental health services to the community, as well as a Head Start program.

“I think there’s been significant improvement, but still a lot that needs to be done,” Griffith said.

Dr. Matt Harris, the executive Director at Project Impact, which works with at-risk youth, wants to see more emphasis on addressing the causes for unrest and inequality in South L.A., instead of only treating the symptoms.

“The inequalities do exist and they will continue to exist until we have come together with a much more comprehensive plan that reflects a research, that reflects our ability to understand what we’ve been affected by, and that we have appropriated the right type of resources and skill sets to deal with those issues,” Harris said.

Rev. Murray said he’s seen positives in South L.A., from financial investment in the area to a change in the mentality of law enforcement.

Murray Center executive director Reverend Mark Whitlock does not believe another uprising is likely to occur. He cites more African American elected leaders, and points out the peaceful protests surrounding the still evolving Trayvon Martin shooting in Florida.

“We probably won’t see anything like we saw back in 1992,” Rev. Whitlock said. “There’s still a group of young people that are more prone to violence than not. But if we look at things in comparison to 1992, no, it’s not going to burn.”

The corner of Florence and Normandie is ground zero of the unrest. This is where rioters pulled Reginald Denny from his truck and beat him.

Just a couple of blocks west from that infamous intersection sits S.C.O.P.E. (Strategic Concepts in Organizing and Policy Education), a grassroots social justice organization serving South L.A.

“Poverty in South Los Angeles is South Los Angeles,” said S.C.O.P.E. organizer Clementina Lopez. “We don’t have access to good paying jobs. Buildings were burned down and empty lots exist there to this day.”

On April 29, 1992, Lopez was at her home with her 10-year-old son at the corner of Adams and Vermont, just north of the University of Southern California. She saw fires burning in her neighborhood, and people with weapons on the roof of a nearby liquor store defending the property.

Out of the 1992 unrest rose Action for Grassroots Empowerment and Neighborhood Development Alternatives (AGENDA). Lopez joined AGENDA in 1997, and the organization later changed to S.C.O.P.E to better reflect its mission.

While Lopez still sees inequality in South Los Angeles, she believes the work done by S.C.O.P.E. and others as the key to moving forward.

“Folks are looking for real change, and we’re hearing that from the residents when we speak to them,” said Lopez, who has lived in the neighborhood for 30 years. “We have hope, and the hope for change is very much alive.”

One example of change in South L.A. is the addition of the Expo Line. After several delays, the light rail line that connects downtown Los Angeles to points west and runs along the northern portion of South L.A., will open on April 28. One day before the 20th anniversary. Earlez Grille sits next to one of the line’s stops.

Earle, for one, sees the path to change and improvement in South L.A. through engagement.

“What I tell a lot of young kids, if you’re not happy with the way things are going, you have to join,” he said. “You have to make change from within.”

“You can’t make change by going out and burning and looting and rioting,” he added.

You must be logged in to post a comment.