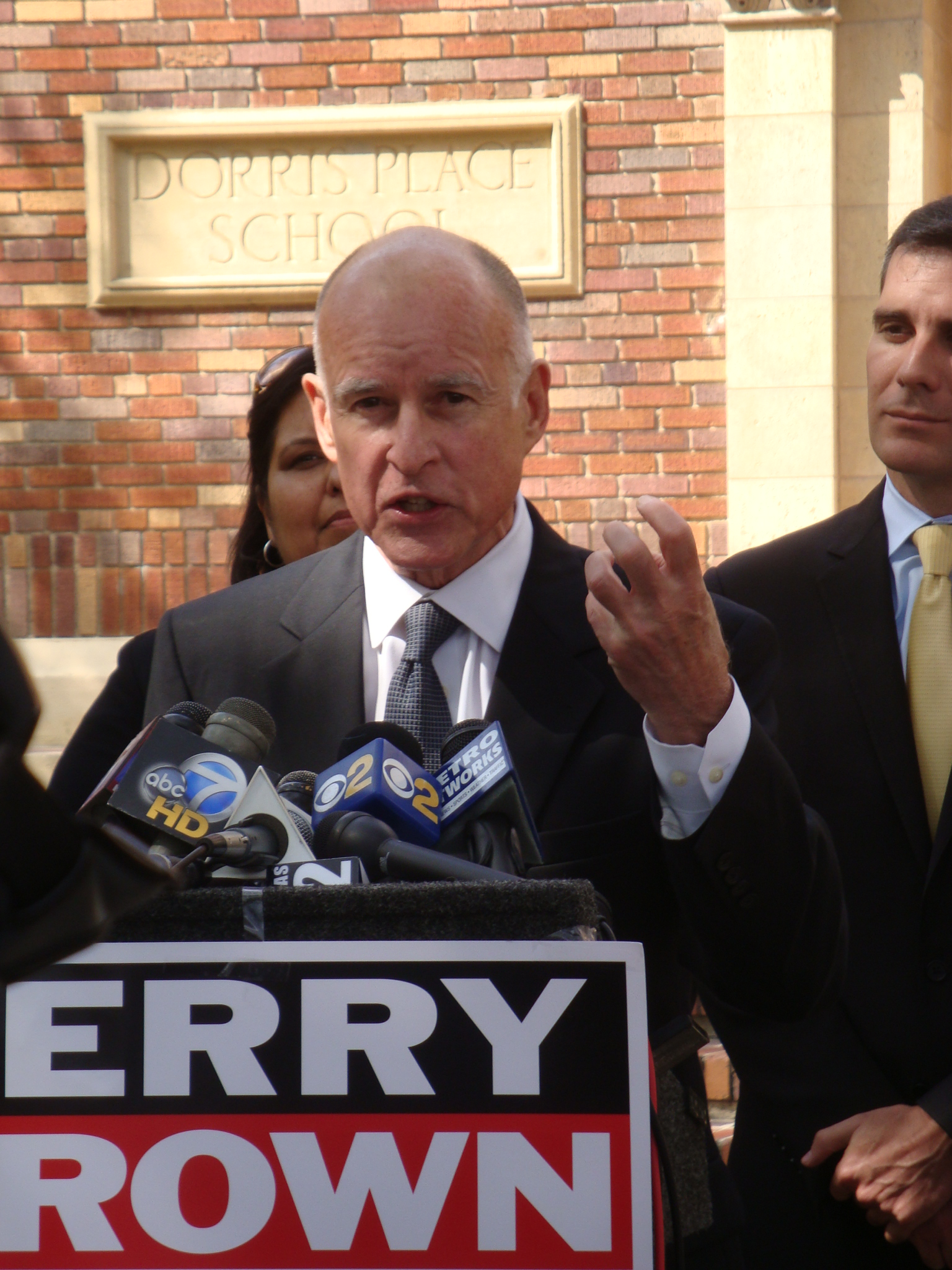

Gov. Jerry Brown is proposing the most far-reaching changes to welfare since former President Bill Clinton and Congress overhauled the program 15 years ago.

Brown wants to cut $1 billion from the program — nearly one-third of its general fund budget — by shortening the amount of time recipients can remain on aid and focusing the state’s cash assistance and child care subsidies on people who are moving from welfare to work.

His plan has won initial praise from the state’s independent budget analyst. But advocates for the poor say it would further marginalize the state’s already struggling underclass. And Democratic leaders in the Legislature have said they will delay any action on the proposal until after the governor’s March 1 deadline, in the hopes that state tax revenues will come in higher than Brown anticipates.

While a common perception of welfare is a program that supports poor, unproductive people, the program has morphed over the past decade into one that provides not just cash grants but job training and services to help people enter the workforce. And more than anything, it is a program that supports children. More than 1 million of the 1.4 million people helped by the program are children.

It is also a program which, while never a major part of the state budget, has shrunk dramatically over the past generation.

In the mid-1990s, when welfare was an entitlement with no work or education obligations and no time limit, more than 900,000 families were on aid in California. But in 1996 then-President Clinton and Congress agreed on a fundamental restructuring of the program. Aid would no longer be open-ended, and states were required to move a certain percentage of their cases from welfare to work.

These changes altered the mindset of the program from one of providing subsistence grants to one that became more of a bridge to employment. In California, recipients were given a five-year time limit (recently reduced to four years) and they got more access to education, job training and child care to help them move into the workforce.

Even the name of the program was changed to reflect the new attitude, from Aid to Families with Dependent Children to Temporary Assistance for Needy Families and, finally, to Cal-Works.

For a time, the changes in the rules and the philosophy seemed to work. They coincided with a late-1990s economy that was bolstered by the technology boom, and the number of welfare cases dropped in half, to 460,000 by 2007.

The cases that remained, however, were the toughest: people whose lack of education, job skills or experience made them very difficult to employ. As the economy slid into a recession, those people found it nearly impossible to find jobs, and they were joined on the rolls by more families headed by newly jobless parents.

The welfare caseload began to grow again. By next year, if nothing is done, about 600,000 families will be on welfare in California. The cost of the program will grow by half a billion dollars.

One reason for that increase in costs will be the expiration of short-term changes adopted in each of the past two budgets. These changes reduced the amount of funding to counties to provide employment services and child care to families while exempting families with a child between the ages of 12 and 23 months, or two children under the age of six, from work requirements.

The Brown Administration says these changes have undermined the program by eroding its focus on work, leaving the state vulnerable to federal penalties levied on states that fail to shift enough families from welfare into the workforce.

In response, Brown has proposed what can only be described as a radical restructuring of the program.

His most dramatic proposal is to reduce the time limit from its current 48 months to just 24 months for people who fail to find unsubsidized employment. The adults would be kicked off aid and denied other services, but the families would continue to collect assistance for the children.

People who found jobs within their first two years on welfare but whose incomes still qualified them for aid would be allowed to remain in the program for a total of 48 months. And they would be allowed to keep more of what they earned. For the average family of three, the change would amount to an increase of $44 a month.

And while those families who remained on welfare with parents working would continue to be eligible for state-subsidized child care, many other families would lose this benefit. On one end, Brown would limit eligibility to just those parents who were meeting the state’s work requirement, leaving many low-income or penniless families out of child care altogether. On the other end of the scale, he would reduce the income eligibility threshold from 70 percent of the state’s median family income to about 62 percent, ending subsidized child care for families earning anything more than twice the federal poverty level. This would result in an estimated 62,000 children losing child care, out of about 296,000 who get it from the state today.

Brown wants the changes in welfare to take effect by October of this year. While the time limits on aid would apply retroactively, Brown proposes giving all recipients six months to find work before kicking them off the rolls. The counties would get $35 million in one-time funds from the state to help people ready themselves for work and find jobs.

But Brown acknowledges that few of the long-term cases would find work. His administration estimates that welfare cases would plummet next year from a projected 597,000 families to just 324,000, a reduction of 44 percent. Nearly 300,000 would be part of a new, separate program giving limited assistance, but few services, to the children in families headed by parents who could not, or refused, to work.

While Brown has proposed asking voters to raise taxes as part of his budget plan, the changes he suggests in welfare would take place with or without the tax increase. The state, he said, simply does not have enough money to do all the things it once did.

Welfare advocates and others say that the cuts will backfire, leaving more children in poverty and leading to social problems that will cost the state far more than the cuts would save in the long run. But Brown says he has no other choice than to propose changes that Democrats would have at one time would have considered cruel.

“We can’t spend what we don’t have,” he said when he released his budget proposal in early January. “It’s not nice. We don’t like it. But the economy and the tax statutes of California make only so much money available. We have to spend it and make tough choices.”