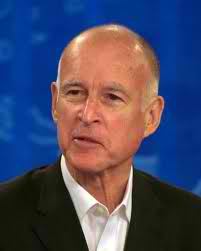

Gov. Jerry Brown’s veto of the new state budget Democrats passed this week represents a gamble that California’ deadlocked Legislature can find its way to a bipartisan solution that has evaded it all year.

Brown, in his veto message, blamed Republicans for refusing to go along with his proposal for a special election at which voters would be asked to ratify the extension of about $10 billion in taxes due to expire at the end of this month.

Brown also slammed his fellow Democrats, indirectly, by describing the budget they passed as filled with “legally questionable maneuvers, costly borrowing and unrealistic savings.” He noted that it would leave the state’s books unbalanced for years to come and add billions of dollars of new debt to the California’s already overburdened balance sheet.

But Brown’s rejection of the budget does not guarantee he is going to get anything better from the Legislature in the days and weeks ahead.

Republicans remain opposed to new taxes, and even to extending the temporary taxes that are about to expire. Democrats remain opposed to making the kind of spending cuts that would be required to balance the budget without those taxes. There appears to be very little middle ground.

Given that deadlock, the budget Brown vetoed Thursday made sense to legislative Democrats. It was their best chance in the short term to protect the programs they believe are vital to California without making concessions to Republicans that would have meant long-term consequences the Democrats could not accept.

This was the first budget to pass since voters last November enacted Proposition 25, which gave the majority party in the Legislature the power to write a budget with their votes alone, rather than the two-thirds majority that was required before.

But that measure left untouched the super-majority requirement for new taxes. And with Republicans opposed to higher taxes, the Democrats’ options are limited.

They could accept a deal offered by some Republicans to place on the ballot a measure that would have extended about $10 billion in temporary taxes that are about to expire. But in order to get that Republican support, Democrats would have to agree to a public vote on a tough new spending limit and rollbacks in public employee pensions, as well as a weakening of the states’ environmental protection laws.

With voters seemingly more opposed to taxes by the day, Democrats might place themselves in the position of holding an election at which their proposed taxes are voted down while the Republican proposals are approved. And even if the voters embraced the taxes, the levies would still be temporary, while the Republican measures would be locked into the state constitution.

That was a deal the Democrats simply could not accept.

The only other alternative for the Democrats is to pass a “responsible” budget on their own that cut spending to live within the revenues the state expects to collect during the next 12 months.

But the wisdom of doing that depends on your definition of the word “responsible.”

To outside analysts using standard bookkeeping principles, that means balancing projected revenues and spending. And with revenues dropping, Democrats would have had to cut deeply into schools, higher education, local government and the safety net.

Those cuts would have come on top of a round of reductions the Democrats approved in March. Those cuts reduced welfare grants and aid to the aged, blind and disabled, cut support for child care and trimmed health insurance subsidies for the low-income working poor. The Democrats also limited in-home support for the elderly and the disabled and cut services for people with developmental disabilities. The March package also cut $500 million each from the University of California and the Cal State University system, forcing another round of tuition increases on students and their families.

And so, rather than doubling down on those cuts, Democrats punted.

They voted to defer nearly $3 billion in payments due to the schools in the next fiscal year to the year after next. The schools would still get the money, but they would get it late. Many districts would have to borrow to cover cash shortfalls caused by the late payments from the state. But on the state’s books for the coming fiscal year, the deferral is as good as a budget cut, because the spending wouldn’t be counted until after the close of the fiscal year.

The budget also included about $1 billion in optimistic revenues assumptions. With tax collections in May running $400 million above earlier projections, the Democrats dedicated that money to the budget and then assumed that another $400 million would materialize next year. They are also counting on $200 million by requiring Internet retailers to collect sales tax on items they sell to Californians.

The Democrats were also hoping that the federal government would help, and the budget relies on $700 million in new payments for the Medi-Cal program that the state says the feds owe California.

Senate Republican Leader Bob Dutton called it an “irresponsible package” that did nothing to change “government as usual” in Sacramento. Brown seemed to agree. Even Democratic leaders in the Legislature conceded that their budget was less than perfect.

Assembly Speaker John Perez, D-Los Angeles, said the plan would close “more than half” of the state’s ongoing gap between spending and revenues, a step he described as “astonishing” given that Californians would pay lower taxes beginning July 1.

Sen. Mark Leno, D-San Francisco, chairman of the Senate Budget Committee, described the plan as the “best possible solution we could develop given the tools we had available.”

Democrats acknowledge that they would still have a hole of about $6 billion to fill in a general fund budget that next year will be around $90 billion. Their plan is to take a tax package to the voters in 2012, in a regular election when Democratic turnout will likely be higher than it would have been in a special election this year.

Many Democrats are hoping that the economy will continue to grow, tax collections will exceed projections, and some of the shortfall will be closed naturally. That may occur, and the state does have a history of economic recoveries that exceeded expectations. But even the most optimistic projections about the economy suggest that the state cannot grow its way out of its deficit. New taxes or lower spending are going to have to be part of the mix.

More ominously, the economy has lately been showing signs of renewed weakness. Employment growth has slowed, housing prices are still dropping, and the stock market is heading lower by the week. These trends could all lead to lower income tax collections and an even bigger deficit next year.

Brown has said since he took office that he did not want to continue the state’s tradition of hoping for the best while putting off the tough decisions required to pass a balanced budget. He is still hoping that Democrats and Republicans in the Legislature will agree to a deal that would extend the taxes until an election is held and the voters have a chance to weigh in.

But nobody, perhaps not even the governor, knows how long he is willing to wait. Once the new fiscal year begins, and payments to vendors and local government are delayed and a cash crunch looms, he might be forced to accept a flawed budget that looks very much like the one he rejected Thursday.

Daniel Weintraub is editor of the California Health Report at www.calhealthreport.org