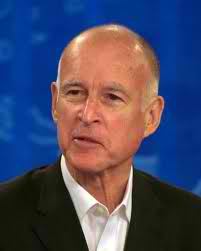

Gov. Jerry Brown wants California voters to weigh in by June on his plan to balance the budget. But the voters, polls show, know next to nothing about the state’s finances, and much of what they think they know is wrong.

That widespread ignorance, understandable in a state as complex as most countries, might play a role in shaping the debate over Brown’s plan, and ultimately the outcome.

Brown is asking state legislators to approve about $12 billion in spending cuts by early April. Then he wants to ask the voters to pass another $11 billion in taxes, mostly by extending temporary taxes adopted in 2009 and due to expire this year.

Brown believes the voters will be more likely to approve the taxes if the cuts are done first. But his approach carries high risk. If the voters say no, the new governor will have used up much of his political capital and he will then be forced to try to get the Legislature to make extremely difficult decisions to cut spending even further.

The voters’ lack of knowledge about even the basic structure of the budget makes the whole gambit even more of a challenge for Brown.

An independent poll by the Public Policy Institute of California last month showed that only 9 percent of voters could correctly identify the state’s largest source of revenue (the personal income tax) and its largest item of spending (kindergarten through 12th grade education).

More than four in ten – 41 percent – believed the prisons were the biggest thing in the budget, while only 22 percent could identify education as the largest item. This is significant, because nearly every poll also shows that prisons are the one thing in the budget voters are willing to cut. If voters have an exaggerated sense of the prison budget’s size, they might also think that balancing the overall budget would be relatively easy if legislators would simply slash more deeply into prison spending.

The voters did better in the PPIC poll on the revenue side. Almost a third, 29 percent, identified the personal income tax as the biggest source of revenue. But the same number incorrectly said that the sales tax was the number one revenue generator. In fact, the personal income tax brings in nearly twice as much money as the sales tax.

A June special election ballot envisioned by Brown would ask voters to extend higher rates on both taxes, so the public’s perception of how high those rates are now, and what role they play in financing state programs, is important.

“The average voter in California doesn’t know the basic facts behind the budget curtain,” said Mark Baldassare, the Public Policy Institute’s president and chief executive officer. “In an environment where people don’t know the basic facts, it is very easy for people to be persuaded that there might be some better plan out there.”

Of course, legislators aren’t typically tested on their knowledge of the budget details, economics or other issues with which they must deal. But they do have more opportunities to get up to speed on these matters should they choose to do so before casting their votes.

Two years ago, then-Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger reached a bipartisan agreement with lawmakers to cut spending and raise taxes, and the governor and lawmakers took part of that plan to the ballot. But the voters soundly rejected a package of measures that would have extended temporary taxes for two years while strengthening the state’s rainy day fund and shifting money from pots earmarked by the voters for special purposes.

Brown hopes to do better, in part by inviting voters into the process from the beginning. In 2009, many voters seemed to see the election as a burden on them. Brown, by promising during his campaign to let voters have a say before he raised taxes, is trying to get them to see the election as an opportunity.

The governor has also used public forums in Northern and Southern California and frequent press appearances to try to educate voters about the stakes involved. While critics say Brown is putting a gun to voters’ heads by threatening to cut spending on schools if the voters don’t pass the tax extensions, the governor says he is trying to avoid issuing threats. At the same time, he does want people to know that the cuts will be far deeper if the temporary taxes expire.

“Many Californians do not know where the state gets its money and what it is spent on,” said Sarah Henry, a spokeswoman for Next10, a Silicon Valley-based non-profit that tries to educate voters about the budget. “There is also a lack of understanding about some of the major proposals being considered by our representatives. But we think people have a great interest in learning more about the budget.”

Through its web site, www.Next10.org, the group promotes a “Budget Challenge” in which participants can try their hand at balancing the budget themselves. Users are presented with various alternatives and try to combine them to shape a balanced budget. The group also recently began publishing a budget question of the day and making it available to other web sites as a way to educate voters.

But Baldassare, the pollster, said that despite years of intensive media coverage about the state’s finances, voter awareness of the issues had barely grown. If Brown’s proposals make it to the ballot, he said, the question will likely be decided as most statewide campaigns are, on the basis of 30-second television commercials.

“Absent having a real strong base of knowledge, people will look to cues for whether there is consensus or conflict,” Baldassare said. “If there is conflict, and it doesn’t matter how much, I think that just creates the opportunity for mistrust, misinformation to take place. It’s always much easier for people to vote no than to vote yes anyway. Voting no is the default for ballot measures.”