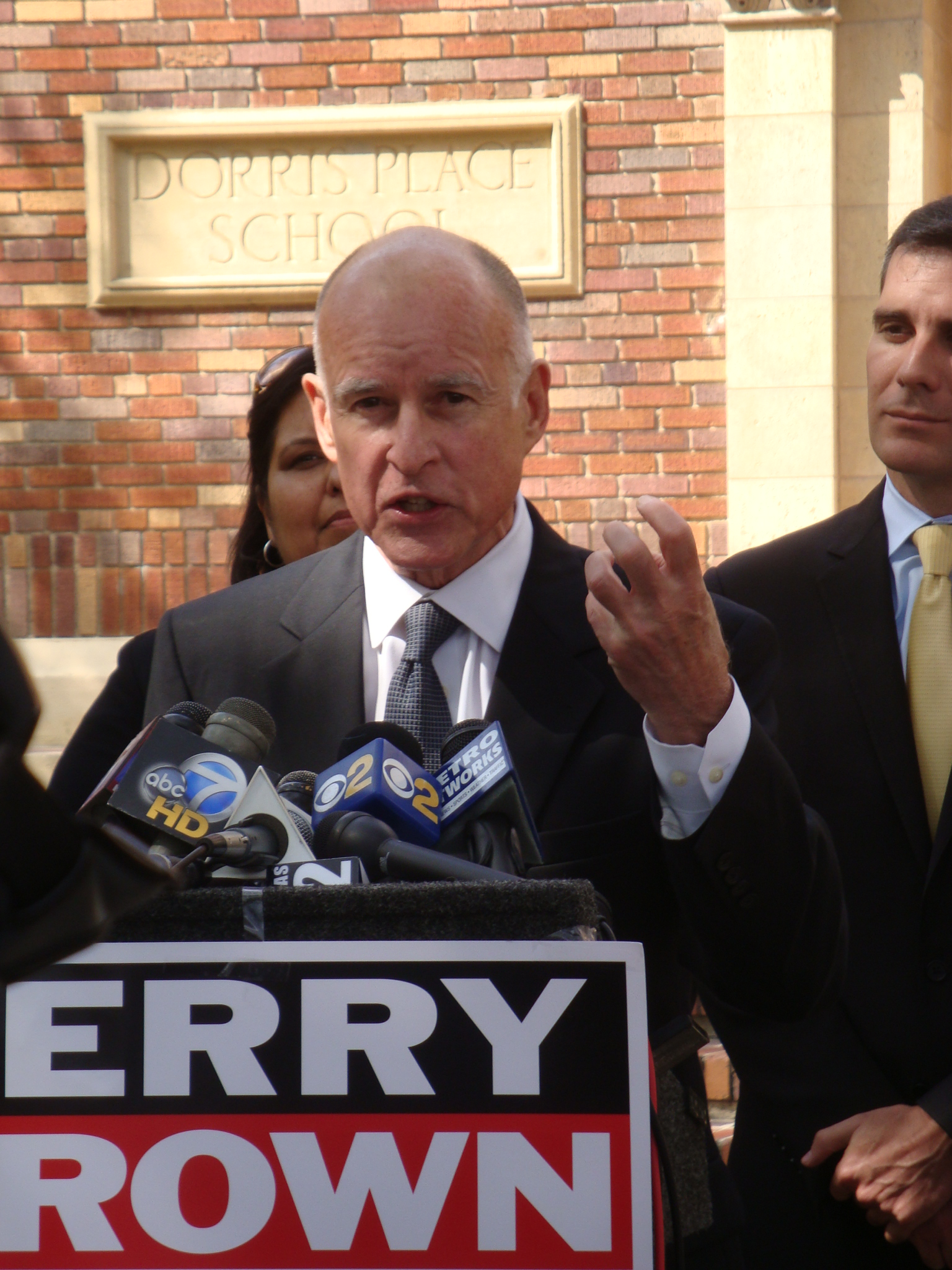

When Gov. Jerry Brown unveils his first proposal to deal with the state’s $28 billion budget shortfall this week, he probably won’t be offering many new ideas. But he will be hoping that a new approach and a different kind of leadership will help him get his plans through a Legislature and a public that were often hostile to his predecessor, Arnold Schwarzenegger.

Like Schwarzenegger, Brown is talking about deep cuts in the health and social service safety net, including reductions in grants to the poor, services to the homebound and health benefits for children in low-income families.

Brown will probably offer no more than the minimum the state constitution requires for kindergarten-through 12th grade education. The state’s public universities will take a whack, forcing them to raise tuition even further.

To find new revenue, Brown reportedly wants to go to the voters to extend temporary tax hikes enacted under Schwarzenegger two years ago, and to unlock some money the voters set aside with ballot measures in years past.

Finally, Brown says he wants to shift some state programs to cities and counties, along with the money to pay for them.

The reason most of this sounds familiar is that there are not too many other options. The state is on a pace to end the current year with a deficit of at least $6 billion and then spend $20 billion more than it will take in next year. The kind of cuts needed to wipe out that shortfall – more than 20 percent on an annual basis – would not be palatable to the people. So Brown is proposing a mix of cuts, new revenue and shifting responsibilities, just as Schwarzenegger did before him.

The big question is whether the Democrats, who now have the power to pass a budget on a majority vote, will be willing to adopt a spending plan that balances without the new revenue they and Brown will be seeking from the voters, most likely in a special election this June. This would be an ugly budget that would cut deeply not just into programs for the poor but into many services that middle-income Californians value highly, including the schools, universities, parks, and local government.

The virtue in this approach, if there is one, is that it would be like a wake-up call to the voters. They would see, for the first time, what level of services they can get within the state’s existing tax laws.

The alternative – adopting a budget that assumes the voters will extend the temporary taxes and thus provide more revenue – would be an easier vote for legislators, but is politically riskier. If the Democrats go to the polls implying that a vote against the taxes will trigger another round of cuts, the voters might well call their bluff, because voters tend not to believe politicians when they say they’ve cut all they can from government programs.

Schwarzenegger took a budget plan to the voters in the spring of 2009 with the support of Democrat and Republican leaders in the Legislature and much of the business community. Brown seems unlikely to have backing as wide as that for the plan he is contemplating now.

Yet if the new governor can explain his plan to the voters, engage them in the conversation, and include them in the process of finding a solution, it is possible he could cobble together a majority of the electorate for what he is proposing. One important constituency that was mostly opposed to Schwarzenegger’s ballot package – public employee unions – would likely support Brown and contribute millions of dollars to the campaign.

But if Brown and his allies do go to the voters in June and lose, the new governor will have spent most of his political capital. At that point he and the Legislature would no choice but to cut spending even further. And those reductions would be unlike anything California has seen before.

This is the first in a series of analyses of California’s fiscal crisis, produced in partnership with the Working Families Summit and the California Center for Research on Women and Families.