Twenty years ago, a shooting rampage that left three emergency room doctors severely injured prompted Los Angeles County officials to increase security staffing and technology at county medical facilities.

That included installing metal detectors at hospital and clinic entrances.

But with national healthcare reform coming next year, the low-income patients who have long depended on county services may soon be able to afford medical care elsewhere, and county Health Services director Mitchell Katz expects increased competition for patients.

In response, he’s trying to make the county facilities more welcoming, starting with removing some of the detectors.

“I think that having medical detectors suggests that these are areas of higher violence than other hospitals and other clinics, and there’s no data to indicate that that’s the case,” Katz said.

“The goal is to have practices for our hospitals like those of other hospitals.”

Katz said a national review of hospital security found about half employ detectors at the entrances to emergency rooms and half use none of the devices anywhere.

By July, Los Angeles County will take down all metal detectors except at the three county emergency rooms, Katz said.

Hospital safety police who now monitor the detectors will be assigned to patrol hospital corridors, increasing the visibility of security forces inside the facility and deterring violence, he said.

Doctors and nurses say the plan makes them vulnerable.

“The person who came in and shot us had a shotgun, a .380 semi-automatic with an 11-shot clip which he completely emptied, a .44 magnum and a hunting knife,” said Richard May, who was wounded in the head, chest and arm in the 1993 attack.

“If there had been a metal detector, he would have tripped off the alarm and nobody would have been shot.”

The gunman, Damascio Ybarra Torres, testified at his trial that he believed county doctors – not the three he shot — had injected him with the HIV virus, part of a secret experiment, and he wanted revenge on doctors as a group. Torres was convicted of attempted murder and sentenced to two consecutive life prison terms.

But long before the shooting, May said, he faced threats from people who seemed nearly as troubled as Ybarra. One psychiatric hospital patient plotted to stab him in the back. More than once, others held knives to his throat, demanding prescriptions for opiates.

When Ybarra opened fire, he also hit internist Pawel Kaszubowski, shattering Kaszubowski’s right arm and grazing his head. Like May, Kaszubowski said his wounds still cause him great pain sometimes, and both men struggle with post-traumatic stress disorder.

Both, now working at the county’s H Claude Hudson Comprehensive Health Center, said they’re baffled by Health Services director Katz’s policy.

“The way you make it more friendly is you treat (patients) with respect. That’s what the bottom line is,” Kaszubowski said.

“If you wait 10 hours, then you are going to lose patience. If you increase the amount of proper personnel and quality MDs and nurses and everybody else, then patients won’t wait as long and they’ll be very happy.’

May speculated that, beyond staving off competition from other hospitals, county administrators may be seeking to reshape their public image in order to compete more effectively themselves when healthcare reform takes effect.

“They want to make a quieter, gentler environment, get a large number of people going there, and everything will be fine,” he said. “But I think they’re setting them up for a terrible disappointment.”

For the present, Kaszubowski said he’s been asking patients what they think of removing the detectors. Not a single person has welcomed the change, he said.

Los Angeles Sheriff Chuck Stringham, who oversees Health Services security, said the detectors are effective.

“Any removal that would prevent the detection of weapons coming onto the hospital campus is irresponsible and frankly unthinkable,” he said.

In 1993, County Supervisor Gloria Molina decried hospital officials’ failure to apply the recommendations of a report on heading off potential hospital violence.

But Molina press deputy Roxane Márquez said the supervisor has full confidence in Katz’s recommendation.

“The department head has said that the detectors can be and should be removed,” Márquez said. “We feel very strongly that it would be a good move.”

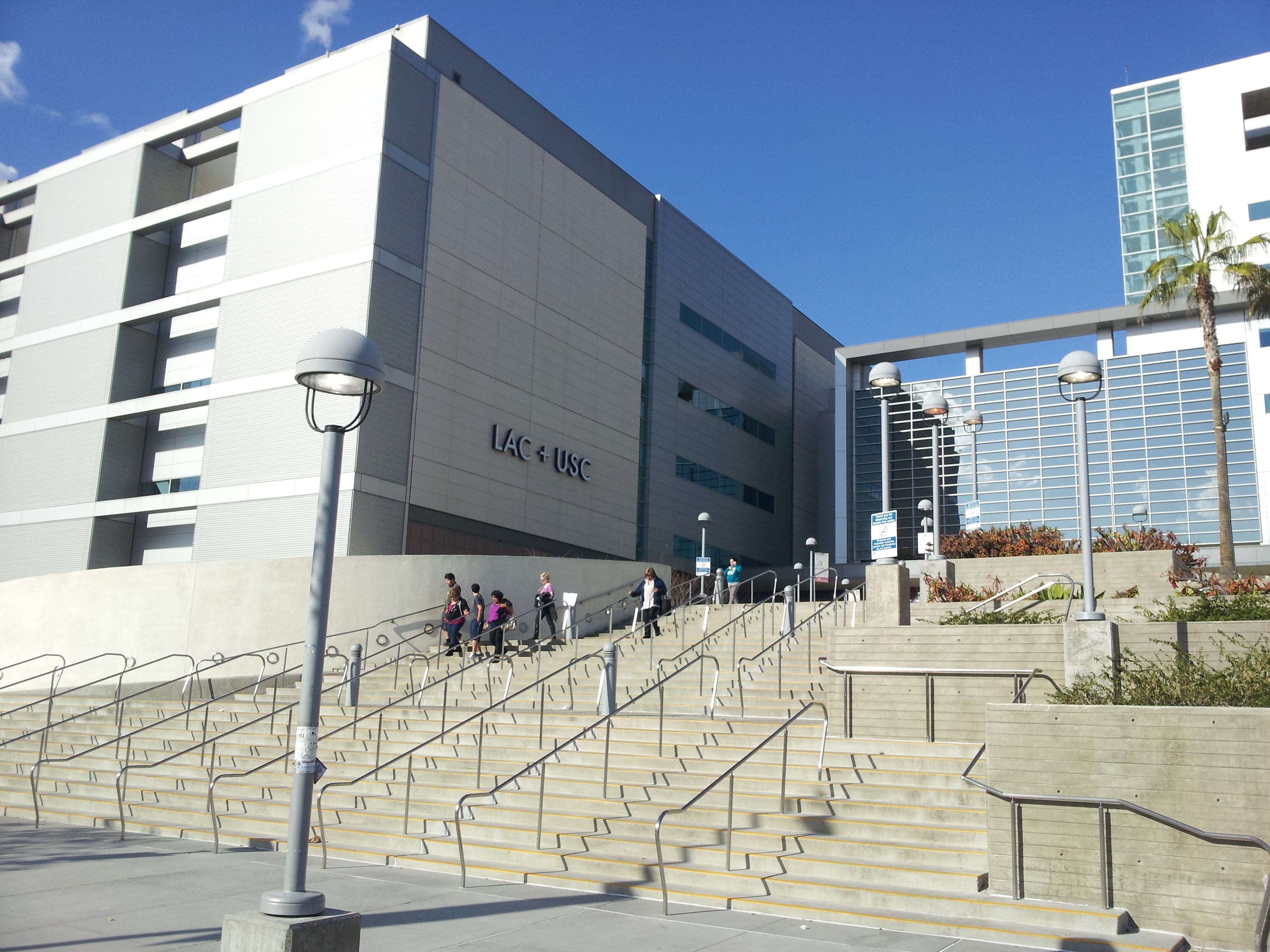

Standing outside the County-USC campus recently, patient John Student said he considers having to walk through a detector a very minor inconvenience.

“It’s a better to catch weapons at the gate than to sweep up after the damage is done,” he said.

In a sidewalk ashtray near where Student stood, a wicked-looking clasp knife lay partially concealed under scraps of paper.

A crowd of people leaving the hospital jostled past the ashtray, and the knife was gone.

“You’ll see people dump that stuff right before they go in through the detector,” said Medical Center plumber Charles Cato. “They do that all the time.”

Sabrina Griffin, a union steward with Service Employees International Local 721, which represents Medical Center nurses, said the union has given formal notice that the new policy is subject to negotiation over workplace safety. Union representatives will meet with Katz next month, Griffin said.

“Come on. This is East LA. We’re not sitting in Cedars Sinai Medical Center or in Beverly Hills,” she said.

“I’m just concerned about everybody’s safety.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.