Infographics by Natalie Jones

Where you live determines your health. This idea has been steadily gaining traction as emerging research continues to highlight the connection between place, lifespan and quality of life. As calhealthreport.org recently reported, for instance, researchers have found that stress can get under your skin and that violence can alter a child’s DNA. The poorest counties in California have the worst health, while the richest, generally, have the best.

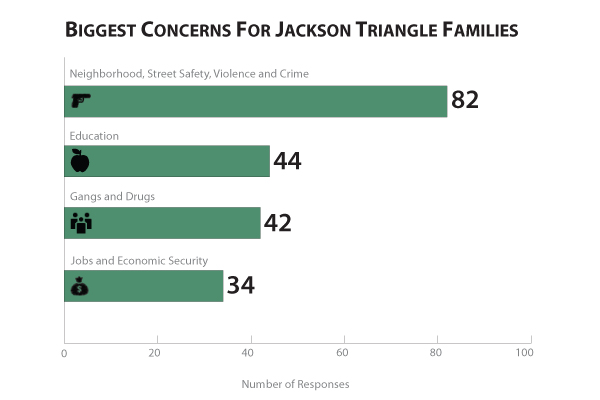

This series of info-graphics looks at the stressors identified by residents in one low-income, high-crime area in the city of Hayward in Alameda County. The Jackson Triangle neighborhood recently won a “Promise grant” from the federal government as part of a program intended to improve the life chances of Jackson Triangle residents.

The grant is significant: only five were awarded in this first round, and the Hayward group beat out more than 200 other organizations in 45 states for this grant (more will be awarded at the end of 2012).

The Hayward Promise Neighborhood (HPN) grant supplies $25 million dollars over five years to provide services to successfully get kids “from cradle to career,” by address the issues that might keep a child from getting a quality education, including health, safety and stability. In the Jackson Triangle, students lack adequate study spaces, the classrooms are overcrowded, and many residents live at or below the poverty level. The HPN aims to cultivate an environment where the schools become the hub of the community, and wraparound services – childcare, parent education, improvements to recreation facilities or bike paths, counseling – help kids realize their potential.

Researchers conducted several community surveys and hosted multiple community forums to collect the information they needed for the promise neighborhood application. Residents consistently expressed concern for neighborhood safety. Data available for 2009 and 2010 indicated a high number of burglaries, vandalism and stolen vehicles in the neighborhood. One survey participant said their biggest concern was “making sure my children can play outside without me worrying about crime or bad people around my home.”

Overall, Alameda county has a high rate of violent crime. Experts say residents in high crime areas have increased stress levels, which may contribute to other health problems, including obesity, heart disease, or asthma. Additionally, residents who perceive their neighborhoods as dangerous may isolate themselves, and lack the necessary social support to cope with the stressors they face.

“I would say the Jackson Triangle is an area where people will avoid if they don’t have to come that way,” said resident Larry Romer. When asked what would most likely get in the way of their child going to college, the fourth most popular answer among survey respondents was drugs and gangs.

The Jackson Triangle community faces high levels of poverty. The cost of housing is so high, and incomes are so low, that nearly a third of the residents contribute more than half their income to housing. Additionally, many of the homes are crowded. More than half of these 591 poverty-stricken households are families with children. The median income for the Jackson Triangle is $48,267, an exceptionally low amount given the high cost of living in the Bay Area (the median income of Alameda county is $66,937).

Unemployment in the area is widespread. Resident Larry Romer said that there used to be a few larger companies – a cannery and a car manufacturing plant – that had employed many people. “People have lost their jobs in these big companies that have closed,” he said. “It’s hard for them to go out there and find jobs so that they can continue to live a decent life. And definitely in the Jackson Triangle, there’s a lot of people without work and that’s the hard part. When they worked at one place their whole life, and now they don’t even know where to go.”

Louise Townsend runs a daycare facility in the Triangle, and she says that even those who do have jobs have a hard time paying for childcare. “There’s a lot of moms who are struggling, and they’re single moms who really need to work to support their family, and they don’t qualify for daycare and maybe they’re on the waiting list,” she said.

Teenage pregnancy rates in Jackson Triangle are significantly higher than the surrounding areas. Pregnant teens are more likely to postpone prenatal care, often receiving late or no care before delivering. They are also more prone to developing gestational hypertension or anemia, and they are more likely to deliver their babies pre-term, which can result in developmental delay, illness or death.

The Promise Neighborhood grant aims to support the community “from cradle to career,” with the goal of creating a college-going culture. Teen pregnancy affects that continuum at two points – the teenage mother and the child. “It really impacts the success of these teens to be able to continue on and graduate not only from high school, but to move on to college, “ said Andrew Kevy, the Hayward Promise Neighborhood Program Manager. Additionally, he said, the program wants to be able to give kids the best start possible, something that is harder to accomplish with a teenage parent.

The issue of kids bringing weapons to school is nothing new, nor is it specific to the Jackson Triangle, but it is a concern. Studies have demonstrated that the presence of weapons at school can foster an intimidating and threatening atmosphere, making it difficult for kids to learn, and for teachers to teach.

This data is taken from the California Healthy Kids Survey, a voluntary survey administered to kids in grades 5, 7, 9 and 11, and it is intended to provide a brief snapshot of school climate.

“It speaks to a lack of connection that kids have to school and the stress level they’re under,” Kevy said. “If your basic needs aren’t being met and you’re not feeling safe and supported at school, you can’t focus enough of your energy on learning and mastering materials.”

The numbers of teenagers feeling sad, hopeless or contemplating suicide were shocking to the research teams, according to Kevy. This data was also compiled from the California Healthy Kids Survey, which demonstrated that these mental health indicators were similar to the statewide results.

“Anecdotally, that’s what we’ve seen,” Kevy said. “Parents are very hopeful for their kids, but we weren’t necessarily seeing a lot of that same hopefulness from the kids themselves, that they would graduate and achieve and go off to greatness.”

He said that optimism among the families varied – some felt hopeful that a school-centered community would succeed and change things, “but a number felt very disconnected with the schools and didn’t necessarily see the school as a way out for their kids.”

Kevy thought that an overall sentiment of hopelessness, particularly in kids, was likely a result of the environment in which they find themselves. “That’s easy to perpetuate when you don’t have a lot of success,” he said. “We’re really trying to break that cycle,” he said.

You must be logged in to post a comment.