Stephanie Estrada struggled into a sitting position from her nest of blankets on the pavement behind a lamp store. She squinted into the beam of a flashlight and swiped at her tangle of graying hair.

Strangers wanting information before dawn? Fine. She’d answer. Soon, the questions had her laughing

Had she suffered an attack while living on the streets?

“Attack or attacks?” Estrada tossed her head. The last time was three weeks ago, a fight with a bigger woman that ended when Estrada was stabbed, she said.

She was matter-of-fact about injecting drugs and drinking. Had she sought medical care in an emergency room in the last three years? That drew a bitter snort.

“Yes.”

How many times?

“Oh my God. Um, I dunno, pick a number. More than 20.”

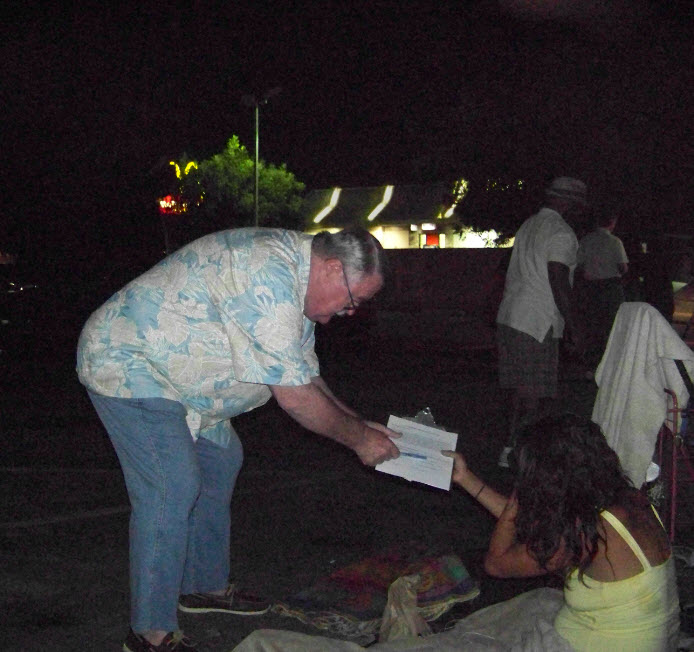

So the answers went over three days of early-morning questioning recently as volunteers fanned out across Los Angeles’ northern San Fernando Valley to gather information about the health of the city’s homeless.

The project was the latest effort of the 100,000 Homes Campaign, a program overseen by Community Solutions, a national spin-off of the New York City homeless service organization Common Ground. The project – implemented in some 95 cities nationwide in the last year – aims to identify the frailest homeless people and move them into permanent housing through the use of a 34-question “vulnerability index.”

Volunteers spend three days interviewing homeless people before dawn, when experience has shown they’re easiest to locate. Questions range from age and length of time on the street to whether a person has liver disease or HIV/AIDS to injuries related to cold weather. From that, the Harvard-designed survey seeks to extrapolate respondents’ health risk, and then find housing for the most vulnerable first.

These are the people who have been on the streets the longest and have such conditions as end-stage renal disease, a history of cold weather injuries, liver disease or cirrhosis, or HIV or AIDS. People who are mentally ill, drug abusers and suffering from a chronic medical problem are considered especially vulnerable.

One Boston study set the average age at mortality among the homeless at 47. But according to Susan Partovi, medical director at Homeless Health Care Los Angeles, records nationwide shows that housing this population cuts mortality rates by up to 500 percent.

“Just putting people into a housing situation, we’ve learned that they do much better than living on the the street or even in shelters,” said Michael Cousineau, a health care policy expert at the University of Southern California’s Keck School of Medicine.

“Keeping people housed, even when they’re using, they’re not taking their meds, but you stabilize them in a house, it decreases their likelihood of using an emergency room,” Cousineau said. “It improves their likelihood of staying with mental health care. It reduces their likelihood of health problems related to homelessness and street life.”

According to the Corporation for Supportive Housing, providing such housing for a year costs a little more than $15,000 per person. By contrast, a city shelter costs nearly $20,000 per person per year. A jail cell costs a little more than $60,000. A psychiatric hospital bed cots $170,455. And providing a hospital bed, on an annual basis, works out to more than $400,000, according to a Corporation report.

In the San Fernando Valley survey, 222 people reported having had been hospitalized in the past year, with an average stay of seven and a half days. That worked out to a total cost of $8.3 million. The survey also recorded 144 emergency room visits in the past three months, for a total cost of nearly $1 million.

Mike O’Gara, a volunteer in the San Fernando Valley survey, said he’s come to believe in housing the homeless. But he said there clearly isn’t enough to go around. As a member of his local Neighborhood Council, a city advisory body, O’Gara said he first got involved in the issue after after parents in his Sun Valley neighborhood complained to the Neighborhood Council that homeless people were overrunning the local park and frightening their children.

The Council endorsed the construction of a 60-unit “permanent supportive housing” building in the neighborhood. Such facilities typically rent one-bedroom apartments to formerly homeless people at a fraction of their monthly public assistance stipend, and often offer medical, mental health, substance abuse and case management services in the same complex.

But, standing in the pre-dawn darkness near the park, O’Gara shook his head.

“Sixty units is just a drop in the bucket,” he said.

John Horn, co-chairman of the San Fernando census, said funding to build such complexes remains tight. Still, resources are increasing, he said. For instance, the Veterans Administration, which has announced plans to eliminate homelessness among veterans within five years, has increased the number of housing vouchers recently.

“I think the most recent allotment that Los Angeles got was five hundred, and we have well more than 500 homeless veterans,” Horn said. “But it’s a start, and that’s all you can do.”

Eddie Sanders, the other co-chair, said by offering increased payments for medical services through the recent Medicaid expansion entitled “California’s Bridge to Reform” may make it easier to provide housing. The $10 billion program includes increases in health care subsidies for the indigent, including the state’s estimated 134,000 homeless.

Nationwide, the 100,000 Homes project has interviewed some 22,000 people and moved about half that number (10,813) into permanent housing, said Jack Maguire, the project spokesman.

“We’re on track,” he said. “The goal we set for year one was 10,000, and we exceeded that. Everybody’s got to keep working together. One of the great things about this campaign is that when someone in Philadelphia figured out something that worked, it used to just be that it stayed in Philadelphia. Now what we’re seeing is that by connecting communities through this network, if someone if Philadelphia figures out something that works, they can share it with someone in Seattle, and someone in Phoenix, and someone in Los Angeles who’s having the same problem.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.