California is the nation’s most populous state, the owner of the world’s eighth largest economy, the home of Silicon Valley and Hollywood, and the global leader in biotechnology. And yet, the fortunes of its state government depend on a small group of people.

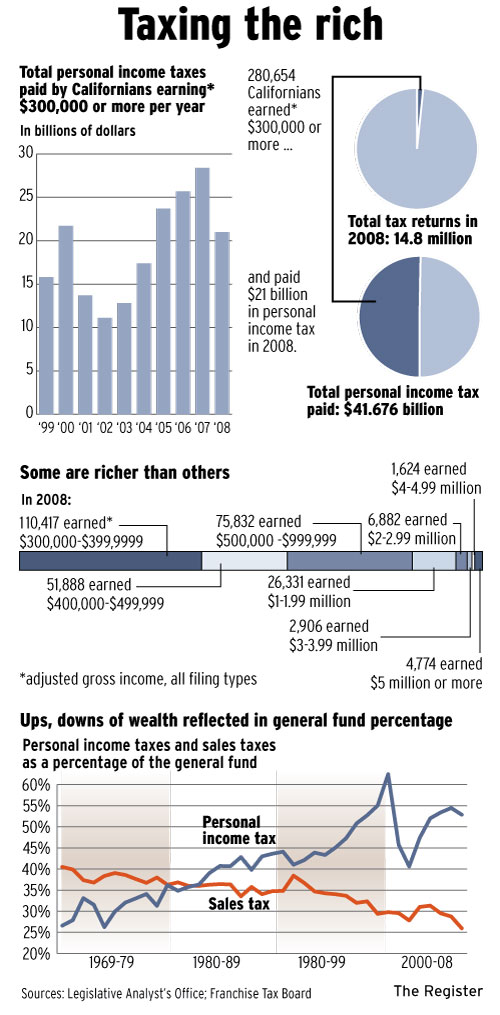

Over the past few decades, California’s budget has become reliant on its richest residents. Roughly a quarter of the state’s General Fund revenue comes from the personal income tax of Californians earning $300,000 or more — a group of tax filers that’s smaller than the population of Stockton.

California faces another multi-billion-budget deficit in part because these rich taxpayers are making less money. Today, many of California’s wealthiest residents earn much of their money not from salaries but from the return on investments. When the economy is good and they’re recording capital gains from selling stocks or real estate, their personal income skyrockets. But when the economy is bad — like it is now — those capital gains dry up. And California suffers.

For example, from 2007 to 2008, the most recent years for which tax data is available, Californians earning $300,000 or more saw their tax liability drop by $7.4 billion, according to figures collected by the Franchise Tax Board. That, of course, coincides with the collapse of the housing market and the larger U.S. economy.

“It’s like building your house on a hillside where there’s traditionally mudslides,” said Curt Pringle, the former mayor of Anaheim and speaker of the state Assembly.

Pringle served on the Commission on the 21st Century Economy, a group formed by former Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, which was tasked with analyzing the weaknesses in the state’s tax system. The task force determined the that the state’s reliance on capital gains of the rich subjected California’s budget to “increased volatility.”

“As a result of this development,” the task force’s final report said, “in the past ten years California has experienced periods of strong revenue growth followed by nearly symmetrical declines.” The state, in other words, doesn’t know what its revenues are going to be from one year to the next.

California wasn’t always so reliant on the rich. In the 1970s, the sales tax, not the income tax, was the state’s top source of revenue. Unlike the income tax, which is progressive, meaning it hits the wealthy hardest, the sales tax is regressive — it has the biggest relative impact on the lower and middle class, who spend a larger share of their incomes on taxable goods.

But fairness aside, California’s revenue stream was more stable when the tax system was more diverse.

Things began to change in the 1980s when Californians adjusted their purchasing habits. Where once Californians spent a large portion of their income on products, like a mouse traps, they now spend more money on services, like pest control.

The eventual switch from a goods-based economy to a service-based one had a monumental impact on the state’s revenues. California’s sales tax applies to goods. It does not apply to services. When Californians started spending more of their income on services than goods, the state lost sales tax revenue. In fiscal year 1982-83, personal income tax overtook the sales tax as the state’s biggest source of revenue and it’s remained that way ever since.

In fact, the disparity between sales tax revenue and personal income tax revenue was solidified in the last decade with the rise of online shopping sites like Amazon.com. With no physical locations in California, the state is unable to force Amazon to charge state sales tax, even to consumers who clearly live in California. The result is Californians are still buying vacuum cleaners and table sets, but the state is no longer collecting sales tax on those transactions made online.

Also, since at least the 1980s, California has followed a national trend that’s seen wealth become more concentrated among the richest residents. In 1987, residents earning $300,000 or more generated just 12.99 percent of the state’s adjusted gross income and paid 21.42 percent of all personal income taxes. Twenty-one years later, in 2008, residents earning $300,000 or more generated a quarter of all the personal adjusted gross income in California and paid half of all the personal income taxes.

Over that time, the number of Californians earning $300,000 or more rose 522 percent, from 45,124 filers in 1987 to 280,654 in 2008. That’s far more of an increase than would be expected from inflation alone.

Jack Pitney, government professor at Claremont McKenna College, said California got this messy tax system through a series of “uncoordinated decisions” by voters and the State Legislature.

“If somebody was designing a tax system from scratch, it’s a good bet it wouldn’t look like what we have today,” he said, adding, “Practically nothing in California politics is by design.”

Now that we have this system, however, arguments have emerged for maintaining the status quo. In fact, the California Federation of Teachers has proposed a ballot measure to increase the income taxes on the top one percent of wage earners by one percent to help close the budget deficit. Their rationale is that a reliance on the rich is equitable — they have the means to pay. A reliance on the sales tax, which impacts the poor, would be unfair.

The risk in that approach is that it would make the state government even more reliant on the fortunes of the wealthy. The next uptick in the economy would fill the state’s coffers even further, and, if the past is any indication, all of that money would be committed to ongoing programs. When the economy slowed again, the fall would be that much harder.

“When the rich sneeze,” Pitney said, “the rest of us catch a cold.”