Photo: Scott Olson/Getty

Dwayne Taylor went to a party at the Ida B. Wells housing project one mid-May night as the Chicago weather was warming to the promise of spring. Once there, according to court documents, Taylor met up with three friends and made a disastrous decision: to rob someone. They left the party and drove around until they found a victim, 21-year-old Tedrin West. Taylor carjacked, abducted and robbed West before shooting him in the back of the head. As her son lay dead in a parking lot, West’s mother called his stolen phone. A man answered.

“Where is Tedrin?” she asked. “Where is my son?”

The reply: “He’s gone, bitch.”

West was murdered in 1993. The group of perpetrators included a 14-year-old boy. The tragedy was part of a wave of youth violence that frightened city dwellers and the nation as a whole in the late ’80s and early ’90s. A graph of violent juvenile crime in the United States in those years looks like a one-sided mountain, climbing up and up with no summit in sight. Juvenile homicide rates jumped from 10 in 100,000 in 1985 to a high of 30 in 100,000 in 1993, just eight years later.

The worst, experts warned, was yet to come. Based on demographic evidence, government officials and criminologists predicted more trouble from a large cohort of children who would terrorize the nation with their violence. These young people were destined to become “superpredators,” sociopaths who would commit crimes without conscience or compunction, according to John DiIulio, the political scientist who coined the term.

“The number of young black criminals is likely to surge,” DiIulio wrote in 1996, “but also the black crime rate, both black-on-black and black-on-white, is increasing, so that as many as half of these juvenile superpredators could be young black males.” These conclusions may sound like outright prejudice today, but at the time, DiIulio’s theory was taken very seriously.

DiIulio also offered a solution to the superpredator problem. “By my estimate, we will probably need to incarcerate at least 150,000 juvenile criminals in the years just ahead,” he explained in his 1995 essay. “In deference to public safety, we will have little choice but to pursue genuine get-tough law-enforcement strategies against the superpredators.”

The nation was already in a tough-on-crime state of mind, but penalties soon became even harsher as the superpredator theory of violent crime took hold. “There are no violent offenses that are juvenile,” Newt Gingrich, then Speaker of the House, told CSPAN. “You rape someone, you are an adult. You murder someone, you are an adult.”

More than 40 states made it easier to transfer children to adult criminal courts between 1992 and 1999. Most states required the transfer of juvenile cases to adult court for certain serious offenses by 1999. Young people who had witnessed violence and abuse in their neighborhoods, who had grown up afraid and become accustomed to it, were now the feared ones.

Searching for a Cure

As youth violence in Chicago soared, epidemiologist Gary Slutkin was working on containing contagious diseases in Somalia and other African countries. Shortly after returning to Chicago following a decade abroad, he began hearing about the disturbing crime trend that had taken off while he was away.

“People started telling me about kids shooting each other,” he recalls, “and I was asking people, ‘What do they do about it?’” Slutkin, who had spent years fighting tuberculosis, cholera and AIDS at home and abroad, was especially curious about how the outbreak of homicide was being contained.

When Slutkin heard that punishment was the response, he was confounded, because punishment does little to prevent homicides. Imprisonment responds to crimes that have already happened and punitive threats aren’t an effective deterrent. “It’s just not the dominant way that people form their behaviors or change their behaviors,” he explains.

Slutkin started investigating approaches to preventing youth homicide. He found they were divided into two extremes. The first was punitive, which Slutkin saw as a profound misunderstanding of the psychology of motivation, especially the motivation of teenagers. Youth behavior, he says, is motivated by peer group norms—in other words, teenagers want to do what their friends do, and potential punishment wouldn’t be enough to make them act unlike their group of friends.

Whereas punitive methods didn’t properly understand the problem at hand, the other approach, which would address the underlying causes of distressed neighborhoods, failed to grasp the urgency of the crisis. Social problems had plagued high-violence neighborhoods for years: poverty, underperforming schools, racism, addiction, the drug trade. But fixes for these intractable problems weren’t forthcoming. Meanwhile, young people, mostly young men of color, were dying at an alarming rate. Consistently, about 70 percent of murder victims in Chicago were African American, according to Chicago Police Department analysis.

African American men weren’t just dying at an alarming rate. They were dying at an epidemic rate, Slutkin concluded after he sat down and began to study maps of Chicago homicides. He noticed something strange—something that perhaps only an epidemiologist could see. Homicides happened in clusters that looked like outbreaks of infectious disease. The maps reminded him of his work trying to contain infectious disease in Africa. Graphs of homicides showed epidemiclike waves of violence by the late 1990s, rather than the steady upward trend seen earlier in the decade. These patterns are typical in epidemics: Infection, transmission and spread happen in waves and clusters. The cycles heat up and slow down. “Like TB and cholera,” Slutkin says, “[violence] produces more of itself, through exposure, witnessing and experiencing.”

“The greatest predictor of whether or not someone is going to do violence is whether they have been exposed to violence and whether or not their friends do violence,” Slutkin says. Recent research based in Chicago supports his point. Yale sociologist Andrew Papachristos found that social networks are much more of an influence on behavior than race or socioeconomic status. Whom you spend time with, he concludes in the 2013 study, shapes how you act and the decisions you make.

Slutkin landed on a strategy that drew on responses to epidemics, particularly tactics he’d used to address to the spread of HIV in Uganda. His program, called Cure Violence, recruited people from high-crime communities in Chicago, many of them ex-cons, as outreach workers and caseworkers. Outreach workers identified people who were spreading the “disease” and tried to convince them to join the program. They worked with people identified as likely to shoot or be shot, information they gathered by keeping a close eye on what was going on in their neighborhood.

As with TB, treatment lasted six months. Rather than with pills, however, violence was treated with intense behavior modification. The method wasn’t easy, but it was simple: Caseworkers reinforced reactions that were reasoned and discouraged rash behavior. The ultimate goal was to change their clients’ sense that violence was a reasonable option and see it instead as an aberration, a terrible choice that carried high risks for punishment and harm to themselves and their families.

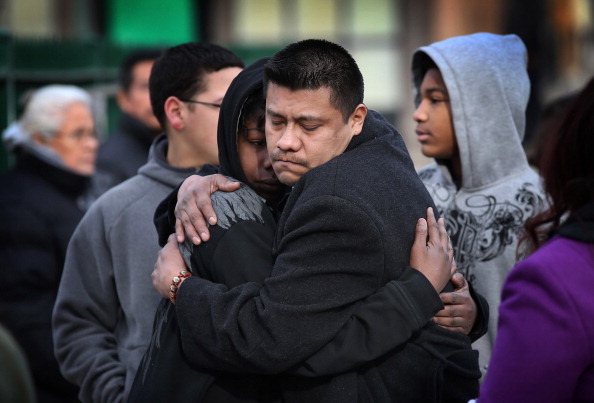

The outreach workers, called violence interrupters, along with the caseworkers, sparked changes so dramatic that they became the subject of a documentary, The Interrupters. Ex-gang members themselves, outreach workers marched with the families of homicide victims and their neighbors to rally community support, mentored young men and women with a round-the-clock, always-on-call intensity and put themselves in harm’s way, going so far as to stand between would-be shooters and coax them away from a fight.

The strategy has brought the crime rate down in three Chicago neighborhoods where the problems seemed intractable, according to an evaluation of the program funded by the National Institute of Justice. Homicide in the hot spots of Auburn Gresham dropped by 21 percent, in Southwest by 23 percent and in West Garfield Park by 28 percent. Evaluators described the change in the last two neighborhoods as “immediate and persistent.” The Institute of Medicine held a conference on violence as a contagion in the 2013, further legitimizing the idea that violence behaves like a virus. Cure Violence is now a model program replicated in cities across the United States and internationally. It became one of the first programs to show that violence could be reduced using a medical model.

The Big Picture

Rates of violent crime dropped dramatically in cities and across the nation following DiIulio’s dramatic predictions in the mid-’90s, a trend called the great crime decline. DiIulio recanted his superpredator theory by signing on to a 2012 Supreme Court amicus brief that challenged the constitutionality of life sentences without parole for juveniles. “The scholar credited with originating that term,” the brief reads, “has acknowledged that his characterizations and predictions were wrong.” Even Newt Gingrich changed his position and is now part of a conservative group called Right on Crime that questioned the sentences of life without parole for people under 18.

No one knows what caused crime to drop in the great decline. Yet, as most of the country was breathing a sigh of relief, people who lived in low-income neighborhoods still had to cope with violence as a fact of life. For many, this has not changed. “Over the last 20 years, at the same time as overall crime has declined,” Chicago blogger Daniel Kay Hertz writes, “the inequality of violence in Chicago has skyrocketed.” Violent crime rates remain significantly higher in low-income Chicago neighborhoods compared to wealthier neighborhoods, Papachristos found in a 2013 study. And violent crimes, including the murder of 16-year-old honor role student Derrion Albert, continue to shock the city.

Cure Violence operates in many of these neighborhoods, but the program isn’t a panacea for homicide. The Cure Violence method, though proven effective, still has limits, says Garen Wintemute, a noted gun violence researcher and UC Davis professor of medicine. The method works best, he says, “on violence that is retaliatory.” Though much violence is interpersonal and retaliatory, even Slutkin readily concedes that about 15 percent is fueled by other motivations, such as the underground economy. And though homicide rates dropped in three Chicago neighborhoods as a result of Cure Violence, two other neighborhoods where the program operated didn’t see a significant change.

Moreover, programs such as Cure Violence require support from public money, a fickle source of funding. “The problem with these approaches is that they are expensive,” Wintemute says. “As soon as the effort slacks off, the results do too.” Cure Violence faced this problem in 2008, when city funding was cut off abruptly and unexpectedly (but it was restored a few months later).

Until recently, the federal government did not fund research into gun violence, Wintemute adds, with profound consequences. The United States doesn’t have gun violence prevention programs in place, he says, “that we could have had a long time ago.”

But a cohort of researchers, including Slutkin, Wintemute, and John Rich, believe that they are headed in the right direction in responding to violence as a health problem. Now, Slutkin says, “the mind-set of the population and government can begin, and needs to begin, to shift in that direction.”

That change in mind-set may have helped both Tedrin West and his killer, Dwayne Taylor. Taylor, who had a juvenile conviction for attempted murder, is exactly the kind of young person the violence interrupters are trying to reform. Taylor clearly was not reformed after his stint in juvenile hall. Following his release, he killed not only West, but also another victim in a separate home invasion robbery. Punishment didn’t change his behavior, and it’s now too late to know if intervention could have changed him and saved his victims.

Second in a series of three stories about violence as a public health crisis.

RELATED:

Hope in a Hidden Public Health Crisis

Stopping Homicides, One Shooter at a Time

The John Jay/Tow Foundation Juvenile Justice Reporting Fellowship helped to support this series.