Deshawn Lamar Clark was released from San Quentin State Prison and returned to where he grew up, near Richmond, Calif., in December of 2005. He was 30 years old.

He returned to Richmond a homeless, jobless man. He owed child support to the mothers of his twelve children. The fine print under his freedom was getting larger. He was staying out of the drug business, but he still lived on the fringes and drove without the blessing of the DMV.

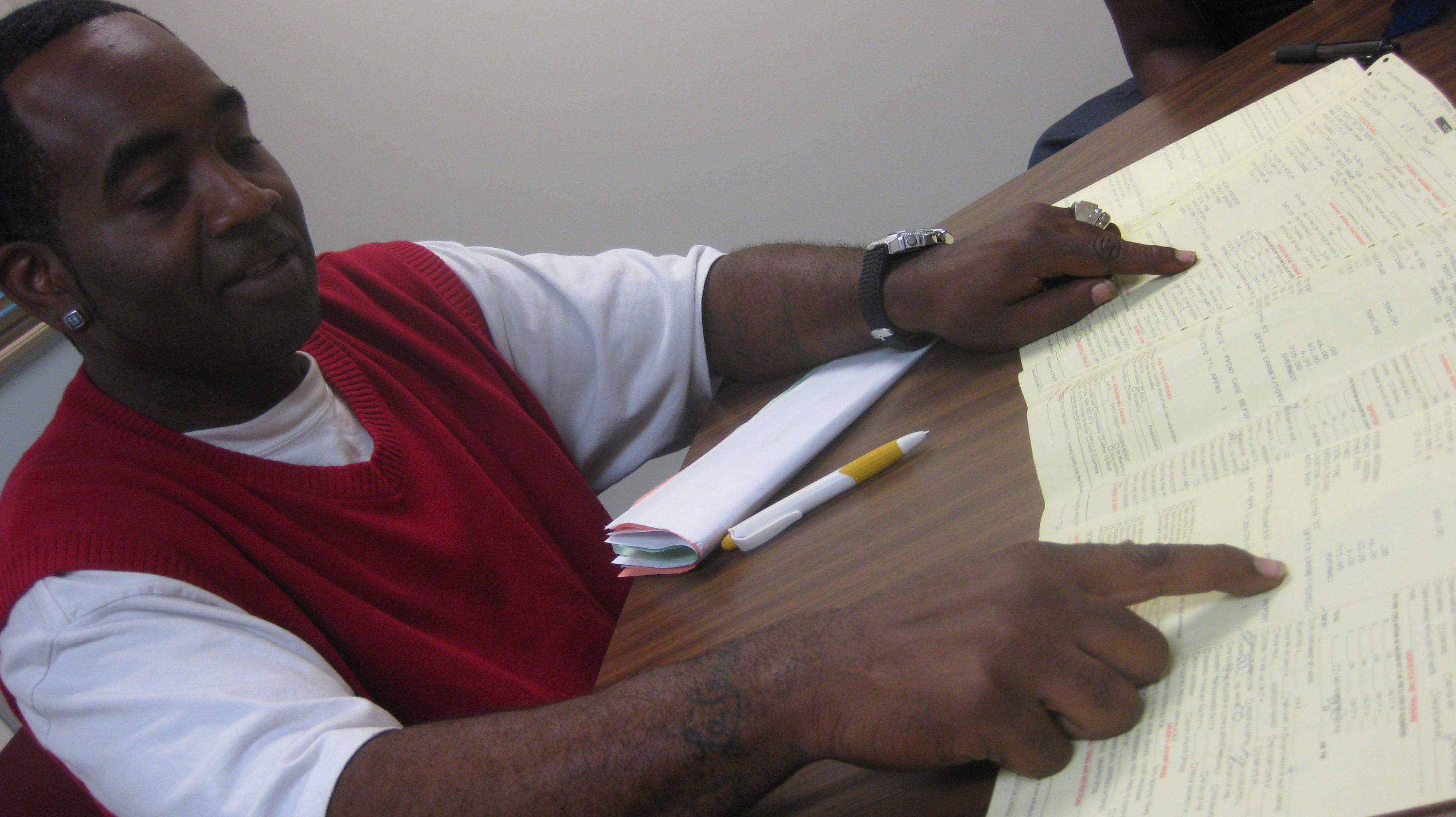

By the time he met Tracy Reed, a caseworker at GRIP, Richmond’s go-to multi-service center and homeless shelter, he had 19 citations totaling over $21,000. In May of 2011, Clark owed more than he’d ever earned, and more than he could ever pay. He’d stayed out of jail, but he’d failed to register his car or acquire a driver’s license.

Last month, Clark and many others had their tickets fixed—legally, by a judge. Contra Costa County’s Homeless Court is for people who have unpaid tickets usually relating to not having a stable address. Once they complete 30 days in a program—whether it’s community service in a shelter (“life skills”), a drug or alcohol rehab program, or job training—they can get their unpaid tickets cleared.

“At first blush it sounds like, ‘you’re clearing up old tickets for some guy sleeping under a freeway?’ said Judge Steve Austin, who started the Homeless Court here and has presided over its monthly sessions since 2006. “But these are all people who’ve been through treatment, who’ve made serious changes to get off the street. At that point, removing the tickets is just us getting out of their way.”

“These people are ready,” said Reed. “People who get off at homeless court don’t get a free ride. They have shown they want to be active participants in society.”

The homeless court model

Homeless Court was created after the veterans group Stand Down conducted a survey among homeless Vietnam veterans. Their most pressing issue turned out to be unresolved criminal or civil cases. Typically, these penalties—like fines for “public nuisance” violations like sleeping, drinking alcohol, or urinating in public—became more daunting to them than accessing food or shelter.

The first session of Homeless Court took place in 1989 at the handball courts behind a gym in San Diego, where homeless veterans tended to gather. Now it has sprouted up in roughly a third of California’s 58 counties, and has yielded savings in court costs. An added benefit to lawmakers, court officials, and taxpayers lies in “alternative sentencing,” said Steve Binder, the San Diego Deputy Public Defender who created the program. Binder said the punitive approach—where unmet citations and fines lead to lockup—makes no sense for people who simply cannot pay.

“The thing is that [regular] courts, while promoting order in our communities, often complicate that order,” he said. “By issuing fines and custody, courts can push people further outside the margins.”

Binder said that Homeless Court is based on the recognition that tickets were never really going to translate into revenue. In fact, he said, penalizing the homeless costs the system far more than it makes.

“These people don’t have the money to pay fines, so they serve time and are literally released back to the streets and it just builds up again,” said Binder. “Nobody’s interests are getting served by that cycle, not prosecutors, not judges, not the defendant. It frustrates everyone.”

In a 2001 study of the Homeless Court program in San Diego, participants said that they would not have resolved these cases on their own and would have “waited until arrested” to go to court. Steve Austin, the arbiter of Homeless Court in Richmond, agrees that punishing people who are living precariously is wasteful.

“Those tickets end up going to warrant, going to jail; that costs a ton of a money to the system,” he said. “The number of public employees who have to touch it is astronomical.”

Plus, he said, people in Homeless Court have already clocked significant hours of community service. “They have been through job training or drug or alcohol programs. They are different from how they were when they got these tickets. We’re just giving them credit for what they’ve done.”

Suspended licenses keep homeless on the street

In Richmond and surrounding towns, the majority of offenses by homeless are transportation related, whether BART or bus fare evasion or driving with an invalid license.

County Public Defender Robin Lipetsky, who supports the Homeless Court and wants to expand it to cover misdemeanors, said the definition of homelessness is broad enough to include people at risk of being homeless, and “couch surfers” like Clark. Homeless advocates called them “precariously housed,” often people who’ve been in the criminal justice system and are trying to get housing, but face steep fines and a public opinion that people who commit crimes don’t deserve support services.

“There’s a whole subculture in society—a number of people who never had a license to begin with or it gets suspended,” said Austin. “They don’t have a place to live, but they’ll get a car somehow, often without a title.”

Mr. Clark’s exorbitant bill, the judge said, is not unusual. “A $100 ticket can turn into a $1000 ticket pretty fast,” he said. “You have an automatic 170 percent penalty, plus $300 if you miss a court date.”

“An enormous barrier that comes up [for homeless people] is these infractions—whether moving or parking violations,” said Kelly Dunn, director of Rubicon Legal Services, a pro bono legal assistance group in the East Bay. “If they don’t get it paid it can easily escalate to $1500, and it comes back to, ‘I don’t have any money anyway, there’s nothing I can do about it, so why bother going to court?’”

Austin said that he’d been aware of this problem—that unpaid tickets often posed the most intractable hurdle to overcoming homelessness—but didn’t know if anything could be done about it.

“Generally judges cannot waive those fines,” said Dunn, the legal adviser. “Judge Austin gets it—he understands how folks can’t get jobs, and all the barriers not having a license creates.”

“People were being prevented from getting a job, housing, and benefits because of these outstanding tickets. And if you’re able to get yourself off the street –then you have this $10,000 fine?” He heard about Homeless Courts at a conference and approached the county’s homeless program director to start one in Contra Costa County.

Tracy Reed is responsible for getting her clients on the Homeless Court docket. She estimates that last month, Homeless Court cleared $75,000 in tickets for her clients.

“When [Clark] came into the GRIP office and we calculated his amount I was astounded,” wrote Reed on her referral letter for her client’s entry into Homeless Court. “He himself was quite embarrassed, and I thought that was a good thing. It showed me he is now caring for himself and willing to make the necessary changes for his life.”

Clark said he spent his twenties “messing up,” but his first detention was at ten years old, when he and an older cousin were busted for stealing gloves in a Montgomery Ward. He grew up touring California’s boys ranches, group homes, county jails, and eventually prisons—Pelican Bay, San Quentin, Folsom—for selling drugs.

“I got out [of San Quentin] with no source of income, no nothing. No information,” Clark said. “When I was growing up, they didn’t just pull you over and check your license.”

“Besides, he said, “I didn’t even have a permanent address.”

“Maybe it’s not knowing how the process works, or not having role models,” said Lipetsky, the public defender. “But I do know once you start getting tickets and fall behind and owe money, you can’t even begin to get a license.”

Reed said people regularly show up at GRIP with similar scenarios—tickets not necessarily related to homelessness per se, but connected to their upbringing in poverty. “Maybe their parents didn’t have a license, so how are they going to know?” said Reed. “Not having a license creates a lack of responsibility, a lack of accountability.”

Her clients at GRIP, like the veterans in San Diego, do get picked out by police for “public nuisance” tickets like loitering and jaywalking. But, she says, increasingly they are young, African-American males, and these fines are par for the course.

“It’s kinda sorta a way of life,” she said. “It has to do with lack of resources, lack of education, and that creates this ripple effect.” Enormous tickets—for driving unregistered cars, with a suspended license or no license—are common.

“Young, African-American people, primarily males—so many young people destroy their license and don’t see any way out,” she said. “Tickets build up and they just say, ‘forget it.’ And they’re driving without a license.”

Without support, she said, they stay on the margins. “Certain populations get left out” of the support system for needy people, said Reed. “They dig a hole and it gets worse and worse.”

After about a year of working at GRIP, Mr. Clark walked out of the small, makeshift Homeless Court in Richmond’s Memorial Auditorium, which was hosting a massive homeless outreach called Homeless Connect 7. He walked straight across the auditorium to the DMV booth and applied for a license. When the sun set that night, he didn’t owe anything—at least not to Contra Costa County.

“I felt so good when I left that courtroom,” he said. “It was almost better than having a newborn. I just wanted to jump for joy. I just wanted to tell everybody.”

A new generation at risk

Clark in fact is telling others about Homeless Court. He does intake at GRIP, explaining to newcomers how they qualify for the Homeless Court program and what documents they need.

Clark has unique assets as a mentor to an emerging population of needy people in Richmond, Reed said —the younger men coming to GRIP, who have started down a bad road but want to turn back.

“We’re used to an older, chronically homeless population,” she said. “People with mental illnesses, substance abuse. We are seeing a lot more young people in here now.” She thinks the phenomenon can be traced to the beginning of the “tough on crime” era, the harsh punitive approaches to law enforcement born in the 1980s. As social services and rehabilitation programs were depleted, people in the criminal justice system upon release have had an increasingly hard time staying out.

The young men he sees “run the streets like I did,” said Clark. “I see a lot of jaywalking tickets.”

He has the credibility needed to reach young people on the street, said Reed. “We need people like Deshawn [Clark] talking to the younger crowd; they don’t always relate to staff.”

“People know him,” she said. “Now he’s the catalyst for people to deal with these kinds of problems. Being legit on the road.”

People like Deshawn Clark are the focus of public safety changes coming to California. Governor Jerry Brown’s County Realignment plan intersects with the Supreme Court decision ordering California to reduce prison populations, in order to provide a constitutional level of health care for its inmates.

As state prisons scramble to reduce their populations, cities and counties will have more of a role in rehabilitation.

If Richmond is really having a renaissance, Reed says some people are being left in the dark. “Richmond needs the human services to keep up with the city’s other renovations,” she said. “Right now there is no housing for the re-entry population,” said Reed. “That’s why we have such a revolving door.”

Clark said that Homeless Court was the first program that ever delivered what it promised. Still, he has not had a home address in his adult life.

Richmond’s housing for the poor, homeless, and mental is at maximum capacity, says Reed, and services for parolees are woefully inadequate.

“They are gearing up for the July reentry of San Quentin’s released,” said Reed, tapping the calendar on her office wall. “Where will they go?”

You must be logged in to post a comment.