Leafy green vegetables, Brussels sprouts, beets and leeks aren’t typically the kinds of foods available at food banks. Fresh foods are hard to salvage for people in need, even though perfectly edible produce that doesn’t meet grocery store standards is often left to rot in the fields. But a Salinas organization, Ag Against Hunger, has developed some innovative methods for distributing fresh produce to food banks.

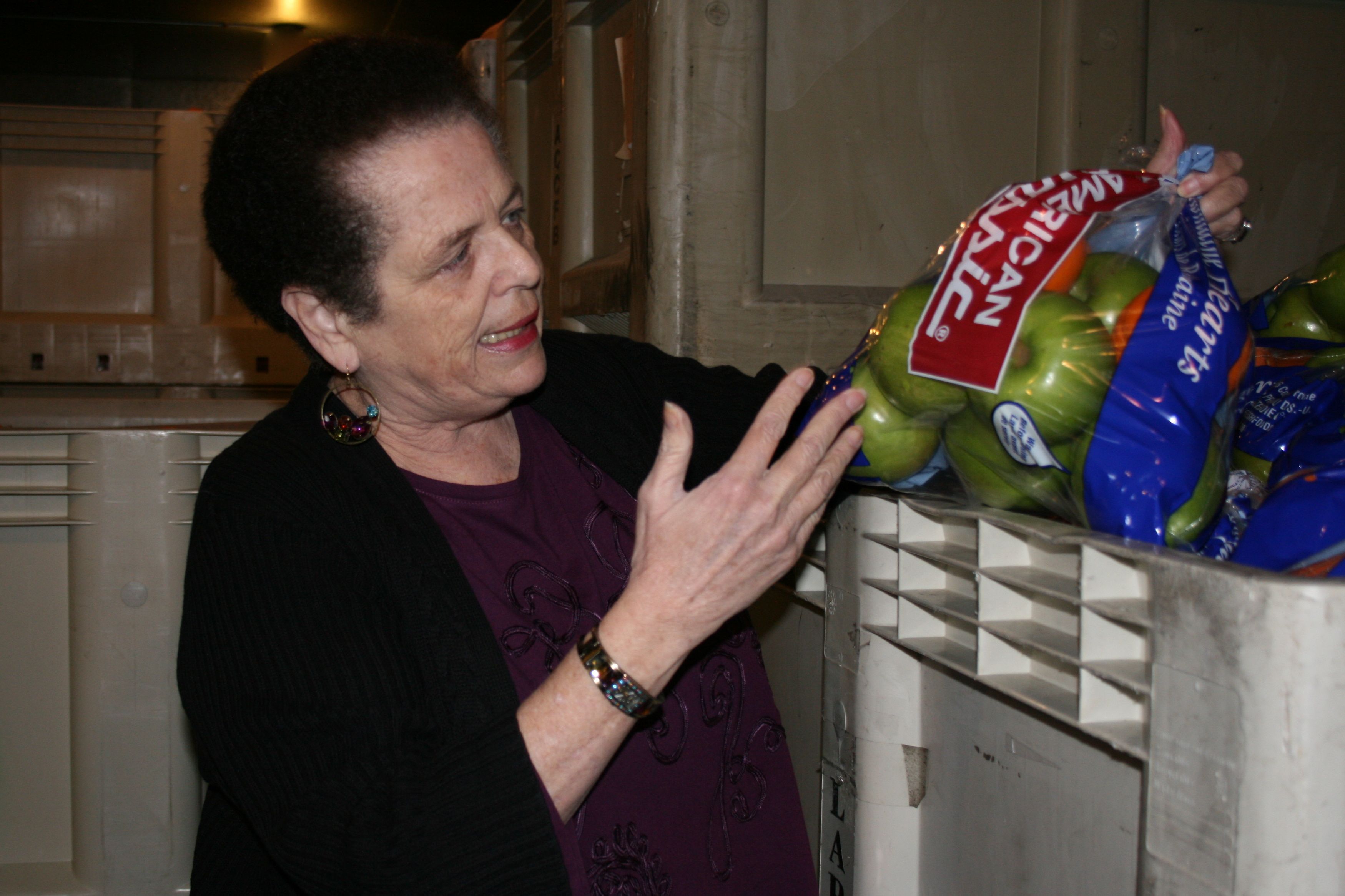

The organization runs a unique volunteer gleaning program, collecting surplus fruits and vegetables that would otherwise be left behind and plowed back into the soil. The produce is perfectly edible, but usually nearing expiration, said Karen DeWitt, executive director for the organization.

“It’s not just a bag of lettuce here and there,” said De Witt. “Last year we collected and distributed 12 million pounds of produce.”

Last year volunteers gleaned 450,000 pounds of fresh food left behind by commercial harvesters. That food was not bruised or spoiled. Produce fit for consumption is left behind for subtle reasons, like the age of the field or the prohibitive cost of harvesting a particular crop. Last year, for instance, a grower contacted DeWitt to ask if Ag Against Hunger would harvest a cherry orchard. A late rain ruined about half of the fruit, and paying pickers to sort it would have resulted in a loss for the farm.

Ag Against Hunger distributes to nonprofits and the food banks serving Salinas, Monterey, San Benito and Santa Cruz Counties.

“There’s a social obligation for us to give out nutritious foods,” said Leslie Sunny, executive director of the Food Bank for Monterey County. While fifty years ago food banks mostly distributed canned goods, “produce is the food of the future,” Sunny said.

Giving out fresh produce is especially important because of growing obesity and diabetes numbers. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, California carries a particularly high obesity burden, with approximately 36 percent of its adult population considered overweight and another 25 percent obese. The Monterey County Obesity Study revealed a 120 percent increase over a twelve-year period for Hispanic children, and sixty-four percent of Salinas’ population is Hispanic.

The keys to maintaining healthy weight, according to the National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, are physical activity and healthy eating, which includes consumption of fruits and vegetables. California’s Central Valley is known as the salad bowl of world, yet only 42 percent of Californians reported eating at least five fruit and vegetable servings daily—a recommended starting point—and less than 20 percent of children, according to the 2009 California Dietary Practice Survey.

Every weekend hundreds of volunteers show up to glean—pick remnant fruits and vegetables—to help bring fresh food to people who can’t afford to buy it. A gleaning session lasts from about 9:00 a.m. till noon. At the beginning of the day, volunteers are taught how to harvest, and then they don gloves and hairnets for a day of work in the fields.

The food and field labor are free, thanks to the more than 700 volunteers. But transporting the food to people who need it costs money. Bins must be purchased, a driver must be hired to transport the full bins of food, and then there are fuel and transportation costs. “We have to move the produce really quickly. We hold it at our cooler, and food banks and other nonprofits come and pick it up,” said DeWitt.

When their 5000 square foot cooler is overflowing and food banks from these counties have all the food they need, Ag Against Hunger reaches out to other California counties and has even provided food to Arizona and Washington food banks, according to the warehouse manager, Cesar De La Torre.

The fresh food needs to be picked and shipped quickly—usually within one or two days—and there is a lot of it to manage, according to De La Torre.

The variety of produce is a boon to food banks across the valley. “We get yams, onions and stone fruit that we normally wouldn’t,” DeWitt said.

One of the ways the Food Bank for Monterey County distributes that healthy food they receive from Ag Against Hunger is through open-air markets, similar to farmer’s markets—but all the food is free.

Once a month, from April through October, at ten Monterey County locations, 200 to 400 families have the opportunity to choose what they take home. Each household walks away with between 50 and 100 pounds of produce.

The help, Sunny said, couldn’t be better timed. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, at its peak in December of 2010, 16.4 percent of Salinas’ population was out of work. Unemployment is highest in Salinas and the Central Valley when growing season halts—December through March.

According to DeWitt, food banks are seeing more working poor—people who have some income, but not enough to feed a family. The Food Bank for Monterey County and Ag Against Hunger work together to meet the needs of one-fifth of Monterey County’s population, according to Sunny, and 18 percent of that population are children under five, living in poverty.

“We’ve seen a tremendous increase,” Sunny said, “in people standing in line to get food.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.