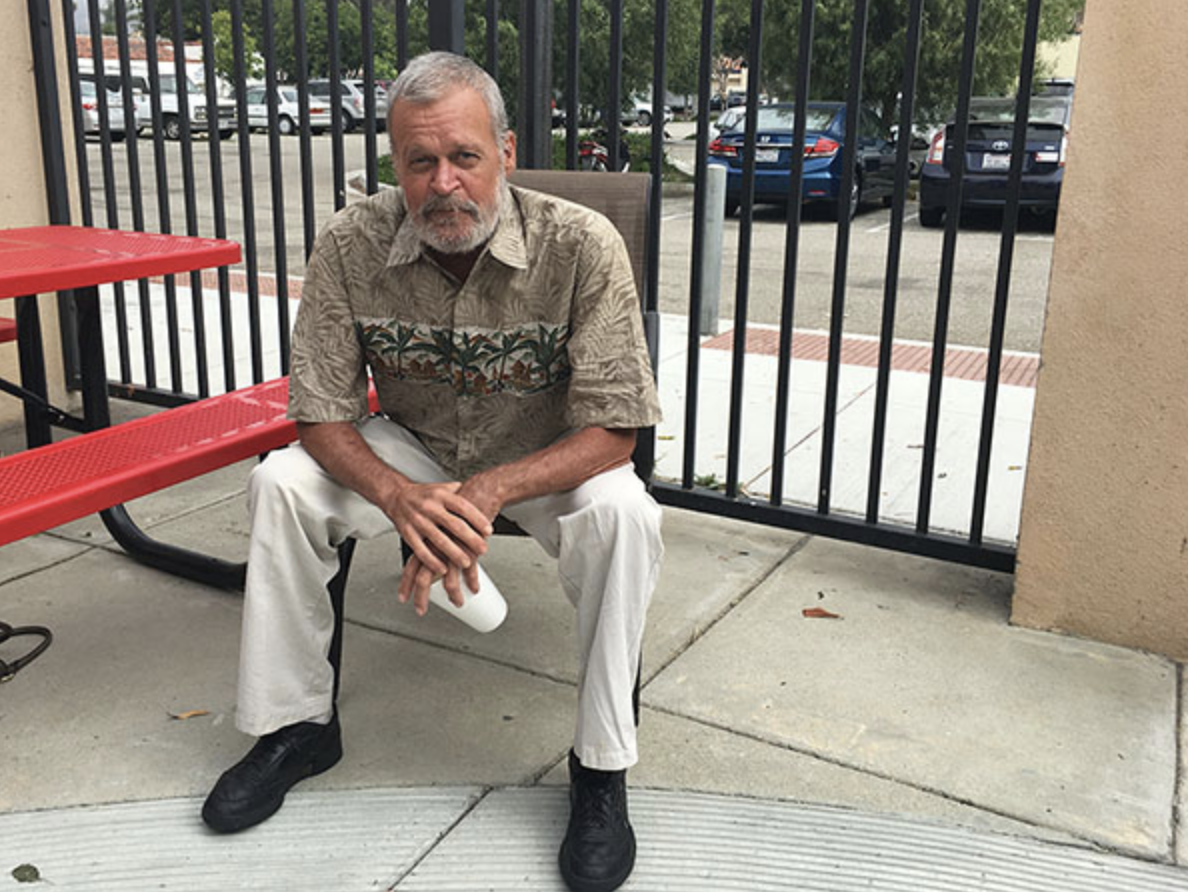

Samuel Raymond Curtis is very familiar with hospital stays.

For the past two years, the 58-year-old homeless man who suffers from problems related to a hernia has been in and out of hospitals in Ventura County more times than he can count. Each time he got treated and released back onto the streets, he said. It wasn’t long before his health started deteriorating again.

“I’d just sit there. I had no place to live,” he said. “I’d just hang out places and eventually the ambulance would come and get me.”

This month, something different happened. Instead of being returned to the outdoors after a stay at Simi Valley Hospital, Curtis was dispatched to Pathway Recuperative Care. Operated by the Los Angeles-based National Health Foundation in partnership with the Hospital Association of Southern California, the newly opened facility provides beds and medical supervision for homeless patients so they can rest and recover after leaving the hospital. The goal is to prevent them from being released and then readmitted to hospital because of health complications related to unsafe, unsanitary and stressful living conditions on the street.

“You and I when we leave the hospital if we were to be there for surgery or an ailment, we would go home and one of our loved ones would take care of us and we’d be able to recuperate and watch television,” explained Kelly Bruno, Chief Executive Officer of the National Health Foundation. “But a person experiencing homelessness, they don’t have a home to go to, so hospitals don’t have an appropriate discharge option for these clients.”

The program’s approximately $700,000-a-year cost is shared by five local hospital systems, which stand to save money if the program succeeds. In the Los Angeles area, where the National Health Foundation operates two other recuperative care sites, the program has saved hospitals and the health care system an estimated $34 million, according to Bruno.

“The growth of the program stemmed from a need, hospitals saying we have a problem, we have these clients, these patients that are ours and we need to discharge and we can’t discharge them appropriately,” Bruno said. “If we discharge them to the street they end up right back in our emergency rooms because they’re healthy enough to be discharged, but not healthy enough to live on the streets. You can’t recover on the street. Yet our other option here is to keep them in the hospital and not be reimbursed by insurance.”

At Pathway Recuperative Care patients receive medical supervision, meals, transportation to doctor’s appointments, and case management from a social worker who tries to connect them with services and housing. The center isn’t licensed to provide direct nursing care. To stay at the facility, patients have to be well enough to walk, bathe themselves, administer their own medicines and take care of their own wounds. A medical coordinator, Bonnie Rouda-Ruiz, works with local hospitals to determine how long patients need to stay, secures follow-up doctors appointments, orders medicines, and keeps track of patient’s vital signs.

Pathway offers six bedrooms, each with two beds, side tables and a private bathroom. There’s a TV, fan, and signs on the wall offering encouraging phrases such as “Today is a Good Day” and “Smile Big and Bright.” Patients get a welcome packet containing essential toiletries such as shampoo, shaving cream and toothpaste.

“It’s not the Carlton or the Windsor, but it’s better than being on the streets or in your car. You get three meals a day, you get snacks, transportation is free,” said Rouda-Ruiz. “People who live on the streets, they don’t have places to bathe, they don’t have hygiene stuff. When they have these items and a shower and their own bathroom it makes them feel human again.”

Often patients come in with multiple needs that have been unaddressed for years, such as a disability, mental health issue or addiction problem, said Social Services Coordinator Debra Stowe. She helps the patients secure identification cards, apply for benefits, obtain medical insurance, access social services, and sets them up with a primary health care provider so they can get regular checkups.

“We have to be as complete and fast as we can to do as much as we can in the time that they’re here,” she said. “Many have been so disconnected so that’s why there are frequent admissions through ER or ER visits, that’s where they run when they need something …it’s kind of a revolving door.”

Recuperative care centers for the homeless are still a relatively new concept. Almost 80 programs operate across the country and are run by a variety of different non-profits, according to a directory published by the National Health Care for the Homeless Council (National HCH). California has 24 programs, more than any other state.

Being so new means state licensing regulations have not had a chance to catch up, Bruno said. National Health Foundation facilities follow protocols established by the National HCH, but there is no license available for recuperative care centers, she said. That means programs cannot get reimbursements from Medi-Cal and Medicare and have to look for alternative funding mechanisms such as partnerships with hospitals or grants, Bruno explained.

The foundation is excited about its new partnership in Ventura because the county’s small size means administrators can better track what happens to patients after they leave the program, Bruno said. In Los Angeles the non-profit contracts with dozens of hospitals, and others don’t participate in the program, so it’s harder to keep tabs on which patients get readmitted to the emergency room, she said.

One of the biggest challenges is finding homes for patients to go to when they leave recuperative care, Bruno and her staff said. Affordable housing is in short supply in both Ventura and Los Angeles counties. Bruno said having an advocate working on the homeless patients’ behalf should help. The foundation would eventually like to expand and provide its own bridge housing to patients have somewhere to live while they wait for a more permanent option.

“Housing is health,” Bruno said. “There’s definitely a dearth of housing and we know that …We’re not going to find what doesn’t exist, but we can hopefully work within the system to help as many people as possible.”

For Curtis, staying at Pathway means finally having a place to relax and heal. He doesn’t have to worry about rain, where to sleep, or how to get to the doctor.

“I’m feeling better,” he said. “One day at a time.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.