By Genevieve Bookwalter

Thirty years ago, kids with cerebral palsy—a loss of certain motor functions caused by brain damage—rarely lived through their teenage years, let alone attended high school.

Now, modern medicine allows them and other students with potentially life-threatening diseases to graduate and live well into adulthood.

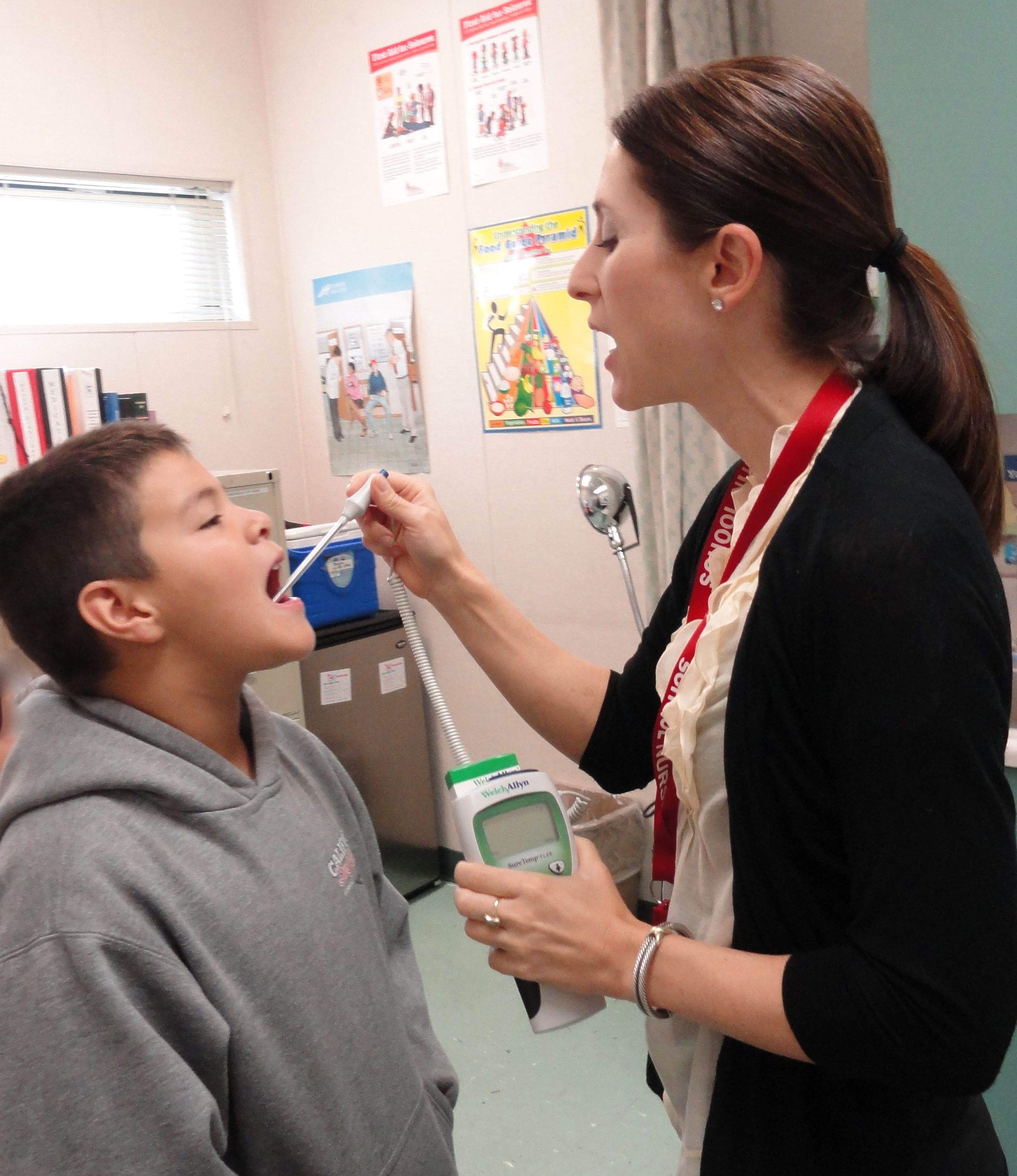

But these medical miracles also have gradually transformed school nurses’ offices from a warm place to get a bandage or ride out a headache to a modern-day care center. Now, nurses regularly do everything from give insulin shots to empty urinary catheter bags.

At the same time, state budget cuts mean the number of school nurses in California is shrinking. As a result, nurses say, they are responsible for more students every year and are largely consumed with keeping “medically fragile” children in class.

The result: they have less time to work with students whose milder symptoms, like a stomach ache or headache, could be signs of larger problems that school nurses traditionally helped find and address, such as bullying, chronic hunger or child abuse.

“Around 30 percent of the students who come into the health office are there because of mental health issues,” said Linda Davis-Alldritt, president of the National Association of School Nurses and based in Sacramento. “So when a child comes in with a mental health issue and the nurse is busy providing insulin to one child, suctioning a (tracheostomy) and providing a gastric tube medication to another child, the child who has the mental health issue may get lost in the shuffle.”

In 2009, the National Association of School Nurses ranked California 42nd in the ratio of school nurses to kids. According to those figures, the most recent available, one California school nurse is responsible for 2,187 students. In Vermont, the state with the lowest ratio, one nurse looked after 311 students.

Nancy Busch, who teaches the online School Nurse Credential Program at Cal State University Fresno and worked as a nurse in Clovis Unified School District for 23 years, said she commonly sees one nurse looking after students in four different schools.

In an extreme example, Busch said, one Southern California district assigns one nurse to 13,000 students. In more rural areas of the state, she said, one nurse could take care of 600 kids in schools that are hours apart.

“The thinner we’re spread, the less we can do,” Busch said.

The shrinking number of school nurses comes as California deals with ongoing financial woes and school budgets shrink. Unlike some states, California does not have a law requiring a nurse in every school, or to oversee a set number of kids.

As result, when schools face ongoing budget crises, nurses are often some of the first positions cut, Davis-Alldritt said.

Over the past three years alone in California, the number of school nurses dropped 9 percent, from 2,901 nurses to 2,474. Meanwhile, the number of students dropped less than 1 percent.

Aside from the state’s recent economic crisis, which has resulted in a sharp drop-off in tax revenue to state coffers, Davis-Alldritt places blame for the dwindling number of school nurses on Proposition 13. The 1978 California ballot measure limited property taxes to 1 percent of a property’s sale price. It also limited the tax’s growth to no more than 2 percent per year — even if the property’s value increased — until the property was sold again.

Many education advocates blame Prop. 13 for hampering school funding, which is paid largely through property taxes. Although overall school spending has increased, along the state’s population since then, critics say that the measure, which remains popular among voters, dramatically slowed the rate of growth of public education spending so that it hasn’t kept up with needs.

“Before Prop. 13, every school in California had a school nurse,” Davis-Alldritt said. “After that the number of school nurses gradually declined, more or less by attrition.”

Davis-Alldritt said her group is looking for outside possibilities to help pay for school nurses. Ideas include everything from designated state funding to money from insurance companies, she said.

Some nurses say they see the latest budget and care challenges as a new reality.

At Fresno’s Central Unified School District, Health Services Coordinator Patricia Gomes said the district is adjusting to less money and increased demand by tapping medical aides and licensed vocational nurses, who have less training than certified school nurses but can administer different levels of basic care and give some medications.

The district currently has 10.5 full-time, certified school nurses; 6 licensed vocational nurses; and six health aides to serve 15,000 students and 22 school sites.

Certified school nurses “really need to be case managers,” Gomes said. Those nurses are the only ones who can help kids with chronic conditions plan their at-school treatment, she said. One student with newly diagnosed Type I diabetes, for example, requires hours of attention to learn how to check blood sugar levels and when he needs insulin.

To further help with schools’ increased demand for medical care, Gomes said teachers are asked to stock their desks with bandages to cover kids’ minor scrapes. Teachers also are encouraged to let kids with headaches, for example, put their heads down for a few minutes during class as opposed to sending them immediately to the nurse’s office.

“Teachers have their hands full too,” Gomes acknowledged. But “if you have a simple headache, that doesn’t mean you have a disease.” The nurse’s office now, she said, must focus largely on critical care.

William Peverill, president of Central Unified’s Board of Trustees and a retired teacher, said he sees the demand nurses face, but the district can’t do much more with its current budget situation.

“It’d be nice if we had (a nurse) at every school,” Peverill said. “I wish we had more teachers and smaller class sizes, too, but that can’t happen.”

Melissa Pernsteiner has a daughter in fifth grade at Herndon-Barstow Elementary School, which is part of Central Unified. She also serves as president of the school’s Parent Teacher Association.

Pernsteiner said she sees the shift in nurse’s priorities and staffing as long-term, as state and local economic woes continue. However, Pernsteiner said she’s been pleased with how Central Unified has handled the challenge.

“I speak to quite a few parents,” Pernsteiner said. “The feedback I’m getting is that the district is doing a good job with the resources it has. I feel that way as well.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.