When Alfredo Mendez, now 18, got picked up by San Diego Police for violating curfew last year, it was a rotten end to a glorious day.

Mendez had arrived home late from school because of an event where he had received three awards for academic achievement and he’d found out he had been accepted to the university he wanted. But the event kept him late and he missed dinner, so he and a friend walked over to the KFC near his house to get something to eat.

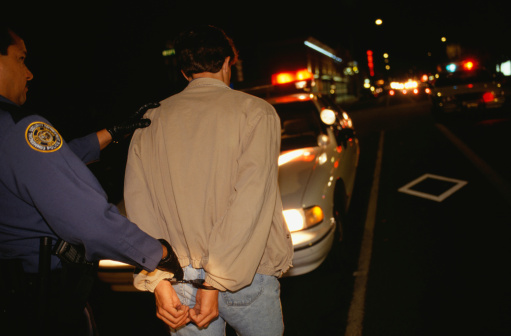

By 10:10 pm, Mendez and his friend, also 17 at the time, were in handcuffs.

“They threw away our refreshments and told us we should be ashamed,” he said. “It was humiliating – If you see someone in the community you know you’re going to see them again, so they’re going to see you after a most humiliating moment where you’ve been handcuffed like a criminal.”

Stories like this leave community advocates at Mid-City CAN (Community Advocacy Network) wondering at the thinking behind curfew enforcement.

“Something’s gone wrong when a kid like Alfredo gets picked up and handcuffed,” said Diana Ross, of Mid-City CAN. “We’ve had the president of the student council at Hoover High School taken into custody. We believe the curfew sweeps target minorities when the police should be targeting criminals.”

But the police in Mid-City see it differently.

“We’re not hurting them, they don’t end up with criminal records,” said Sgt. Jesse Cesena, who heads Juvenile Services in the Mid-City Division. “We’re here to get the kids off of the street before they become victims. We don’t want even one of our kids to end up being shot, stabbed or killed.”

Cesena notes that the police work closely with service providers to help strengthen families and keep the kids moving in positive directions.

But Professor Michael Males of the Center for Juvenile and Criminal Justice, an expert on curfew sweeps, says that connecting kids and families with services is commendable – if they need it. Yet curfew sweeps are like random checkpoints, he says, where everyone gets arrested, not just people who are doing something wrong.

“Curfews are bad policy because they make being under 18 a criminal offense,” he said. “The police already have the tools to arrest people who are drunk in public or soliciting for prostitution or starting fights – and those people should be arrested regardless of their ages. But curfew sweeps mean that you can be arrested for your age alone, and that’s just bad policy.”

Sweeps push kids into feeling victimized by the police, and push communities into believing their kids are being criminalized, Males said. His perception was echoed at a recent community meeting where organizers declared that San Diego police conduct sweeps only in divisions where minorities are the dominant group.

City Heights, where the curfew sweeps occur, is one of the most ethnically diverse neighborhoods in the nation. About 54 percent of the population is Hispanic, 16 percent is Asian (Vietnamese account for 9.9 percent of the population), and 16 percent are African or African American, according to American Community Survey statistics. Just 20 percent of the residents are white, according to the American Community Survey of 2010.

About half the 26,200 households in City Heights have incomes of under $35,000, and the families are larger and more likely to be single parent households, according to U.S. Census statistics.

And the area has among the highest percentage of people under 18 in California: where the statewide average is about 28 percent, nearly 33 percent of City Heights residents are under 18. More than 70 percent of the households have limited English proficiency, according to a California Endowment public health survey.

But Sgt. Jeffrey Pace, an administrator for Juvenile Services across the nine police regional divisions in San Diego, insists that the department’s curfew enforcement is even-handed.

“Every division does curfew sweeps,” Pace said. “The curfew sweeps are based on crime trends in the area. You don’t just go to enforce curfew, you do it to get a handle on the crime trends in the area.”

Police look at crimes where kids are victims and go from there, he said.

“In more affluent areas, where kids have access to vehicles, there are more DUIs and crashes and kids driving when they only have a learner’s permit, so we do vehicle checkpoints,” he explained. “We aim to prevent juveniles from becoming victims – we want to make children safe.”

In neighborhoods like Mid-City and Southeast San Diego, the crimes against kids are usually street crimes, including assaults, rapes and robberies.

Most of those crimes occur immediately after school and are handled by school district police. The ones that happen later fall to the city police.

“In Southeast, we had three or four juvenile deaths every summer and every one of them was after 10 pm,” Pace said. “A lot of the criminals here are minors too, and they see their victims around the neighborhood.”

At a sweep held June 21 in Mid City, the kids who were caught were taken to Cherokee Point Elementary School, where they were processed and then waited for their parents to come get them.

Cherokee Point Principal Godwin Higa worked as a volunteer that night, making sure things worked smoothly. He said he has worked on the sweep nights for four years, with the highest number of kids he’s seen come in in cuffs at 85.

The vast majority of the kids are Hispanic and African-American, he said. He understands that raises concerns of community advocates.

“It looks punitive and it should – the police follow procedure, and the kids are handcuffed and searched,” Higa said. But the streets late at night, he says, are a dangerous place for children, even teenagers. “We’ve had kids come in very drunk or high, which makes them even more vulnerable.”

Higa says he believes the police work to help the kids and their families.

“We have so many overwhelmed parents, so many good kids who need more family structure, so many parents who don’t know what their kids are doing,” he said. “The sweeps give us a chance to connect them to services that can really help.

“You see the parents come in angry and upset and then they see the services we can offer them and they are surprised – a lot of parents don’t know how much help is available.”

Sgt. Cesena, of the Mid-City Juvenile Services Division, points to the array of service providers that include mentorship programs that pair kids with adult mentors, family counseling and parenting classes available in a half dozen languages, and even programs for girls who are at risk of or who may already be victims of sexual exploitation.

“We see kids who are first generation to speak English who are serving as translators for their parents, so the parents are socially isolated and don’t even know their kid is breaking the law,” Cesena said. “We see lots and lots of single parent households where the mom is working hard at paying the bills and trying to raise her kids and she just runs out of energy to deal with the kid who gives her a hard time.”

Cesena says the juvenile officers and the social services groups spend a lot of time interviewing the kids and their parents to try to figure out which of the two dozen service providers can best help the families, so parents not only go home with their child but with an array of contacts to help them.

But, for the Mid-City community and Males, getting help for the kids and families that need it still doesn’t justify the number of good kids whose only crime is being out after 10 pm.

“You can accomplish those goals of getting services for families without taking a shotgun approach and rounding people up for their age,” he said. “Being under 18 is not a cause for reasonable suspicion.”